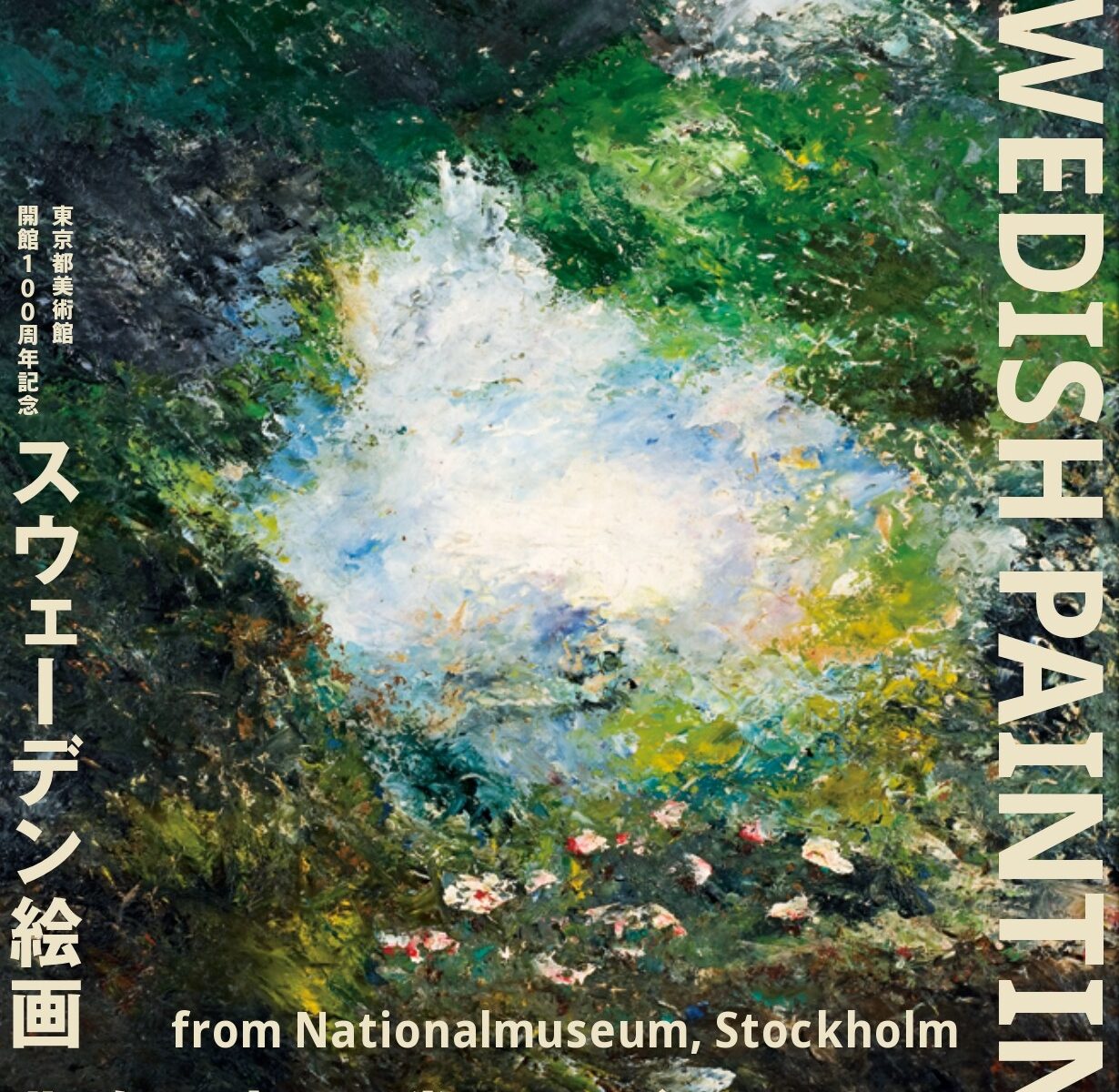

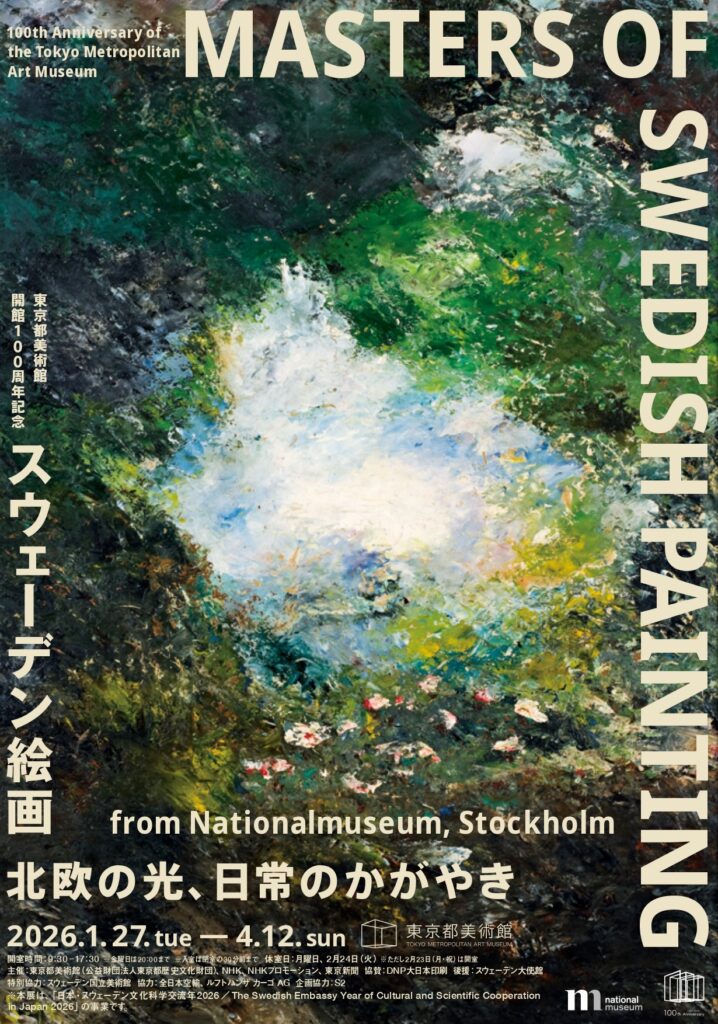

Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum

The exhibition "Swedish Paintings: Nordic Light, Everyday Brilliance" will be held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (Ueno Park, Tokyo) from Tuesday, January 27th to Sunday, April 12th, 2026.

Starting at 10:00 on Friday, November 28th, we will be selling discounted weekday tickets and tickets with original exhibition merchandise. These will be available until stocks run out, so don't miss out!

Weekday-only tickets

❖ [Weekdays only] Advance pair tickets

This is a set of two general advance tickets at a great price.

You can purchase this ticket for 200 yen cheaper than regular advance tickets (600 yen cheaper than purchasing a regular ticket).

Sales price: 4,000 yen (tax included)

Sales period: November 28th (Friday) 10:00 ~ until sold out

Sales location: Available at ARTPASS and other play guides

*This is a set of two general advance tickets ( available only on weekdays ).

* Only one set per person can be purchased.

*This ticket can only be used on weekdays. It can also be used by one person on different dates.

❖ [Weekdays only] Ticket with audio guide

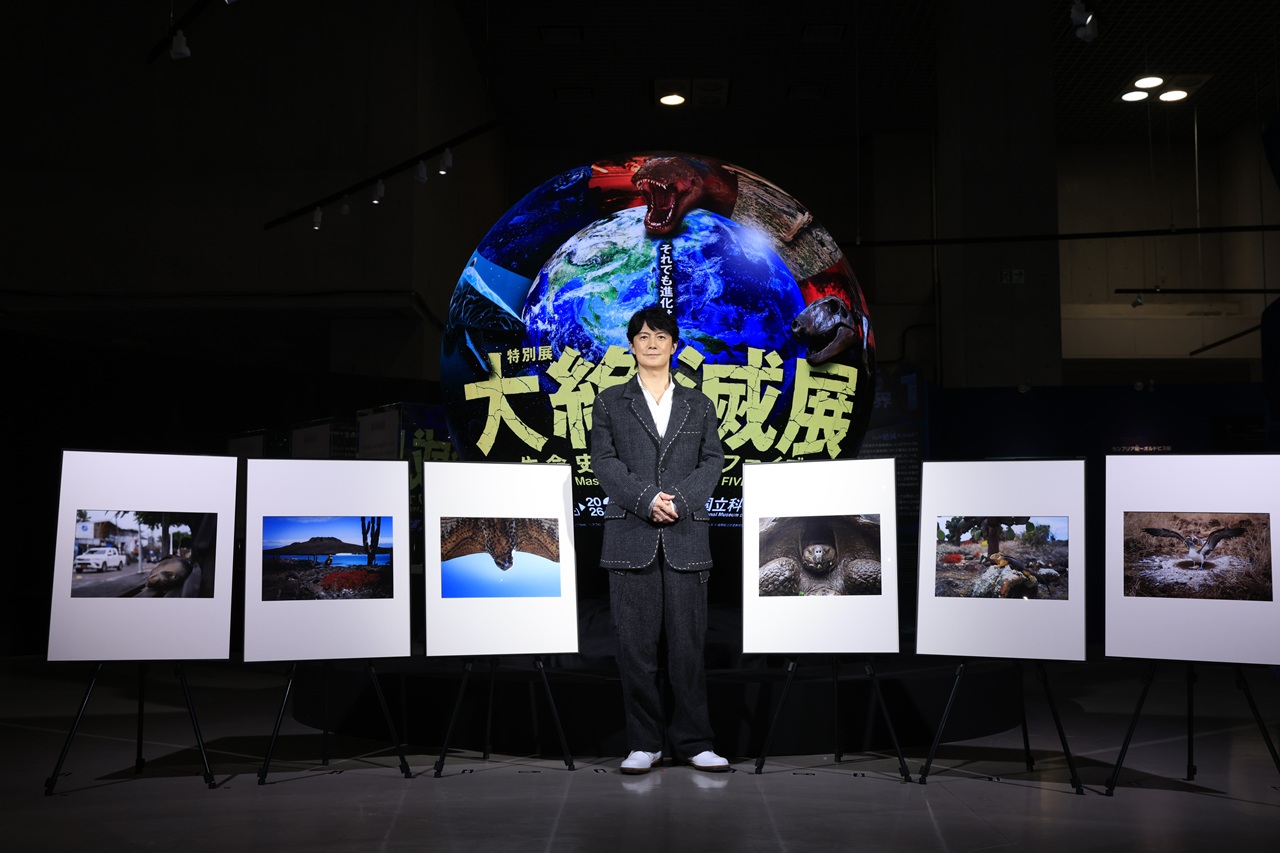

The navigator for the audio guide for this exhibition is JUJU, who has experienced the charm of Nordic items and culture as the MC of the NHK program "The World is Full of Things I Want."

With narration by voice actor Hino Satoshi, we will explore the charm of Swedish paintings!

This is a great value ticket that includes one general advance ticket and one audio guide exchange ticket.

[JUJU profile]

She made her major label debut in 2004. At age 18, she moved to New York, where she experienced a variety of musical cultures, including jazz, hip hop, club music, and soul, and launched her career as a singer. While releasing numerous hits such as "If You Want a Miracle…" and "Yasashisa de Afureru Youni," she has also attracted attention for her life's work of conveying stories through song, singing classics that transcend genres, Japan and the US, and generations, including the Japanese cover album "Request" series and the jazz album "DELICIOUS" series. In spring 2026, she will release the Western cover album "Showa Western Music: Jun Kissa JUJU 'Time Travel' produced by Masataka Matsutoya," and will embark on a nationwide hall tour to promote the album, "Junkissa JUJU 'Time Travel' directed by Masataka Matsutoya," starting in June.

Sales price: 2,700 yen (tax included)

Sales period: November 28th (Friday) 10:00 ~ until sold out

Sales location: Limited sale at Lawson Ticket

*This is a set ticket that includes one general advance ticket and one audio guide exchange ticket ( both valid only on weekdays ).

*Only one ticket can be purchased per person.

*Audio guides will be available for rental at the entrance to the venue only on the days and periods when the exhibition is open. The app version cannot be used.

Goods set ticket

❖Ticket with original sauna hat

Appreciating art is a luxurious time to "harmonize" the mind. This ticket includes an original sauna hat to deepen that "harmonizing" experience. The hat, made from high-quality Imabari towels, is decorated with embroidery of the Dalahäst, a traditional Swedish craft known as the "horse that brings happiness." In Sweden, saunas are called "Bastu," and are said to be an important time to reset the mind and body. Get off to a lucky start in the coming Year of the Horse with the Dalahäst, the horse that brings happiness!

・Unisex (free size)

・Material: Imabari brand, 100% cotton

Antibacterial and deodorizing fabric (SEK mark certified)

・Country of manufacture: Japan

Sales price: 7,000 yen (tax included)

Sales period: November 28th (Friday) 10:00 ~ until sold out

Sales location: Limited sale at Lawson Ticket

*Sales will end once the planned number of tickets is reached.

*The image is for illustrative purposes only and may differ from the actual product.

*The original sauna hat can only be exchanged at the special shop within the venue on the opening days and during the opening hours of this exhibition.

*Available in the limited color (navy) for the goods set ticket.

❖Ticket with original Kewpie costume

This ticket comes with an original costume Kewpie doll dressed in the official Swedish national costume. It features a blue dress, yellow apron, and white hat. It's 100% Swedish! This adorable Kewpie doll is exclusive to this exhibition and is packed with the charm of Sweden.

・Body size: Approx. W27 x H36 x D16 mm

Material: Body: ATBC-PVC, Fabric: Polyester

Strap/Polyester, Iron, Brass

・Country of manufacture: Japan

Sales price: 3,200 yen (tax included)

Sales period: November 28th (Friday) 10:00 ~ until sold out

Sales location: Limited sale at Seven Ticket

*Sales will end once the planned number of tickets is reached.

*The image is for illustrative purposes only and may differ from the actual product.

*The original costume Kewpie can only be exchanged at the special shop within the venue on the opening days and during the opening hours of this exhibition.

*The strap color (orange) is available only with the goods set ticket.

How to purchase

●Official ticket ARTPASS

●Electronic ticket "ASOVIEW!"

*When entering, you will need to complete the entry procedure on your smartphone. You will not be able to enter with a printed ticket or a screenshot of the screen.

● Electronic ticket "Sma Ticket"

*When entering, you will need to complete the entry procedure on your smartphone. You will not be able to enter with a printed ticket or a screenshot of the screen.

*To use Smart Ticket, you must install the ePlus app (free). Please check the recommended environment before using.

How to purchase Smart Ticket: https://eplus.jp/sf/guide/spticket

◎If you purchase your ticket at any of the ticket agencies listed below, you will need to get a paper ticket at a convenience store. You will not be able to enter by presenting your payment history or a screenshot of your ticket.

Please check the website of each retailer for fees and sales end dates before purchasing.

● Seven Ticket

In-store sales: Seven-Eleven stores (in-store multi-copy machines)

How to purchase in store: http://7ticket.jp/go/i000008

● Lawson Ticket

L code: 34607

In-store sales: Loppi machines in Lawson and Ministop stores

How to purchase in store: https://l-tike.com/concert/mevent/?mid=391437

● e+ (eplus)

In-store sales: FamilyMart stores (in-store multi-copy machines)

How to purchase in store: https://support-qa.eplus.jp/hc/ja/articles/6638367888665

● Ticket Pia

P-Code: 995-747

In-store sales: Seven-Eleven stores (in-store multi-copy machines)

How to purchase in store: https://t.pia.jp/guide/sej-t.jsp

● CN Play Guide

In-store sales: FamilyMart stores (in-store multi-copy machines)

How to purchase in store: http://www.cnplayguide.com/familymart/

●Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum

Advance tickets will be sold at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum Museum Shop.

Regular tickets for the duration of the exhibition will be sold at the ticket counter of Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum.

During busy times, it may take some time from the time of purchase to the time of entry.

[Exhibition Overview]

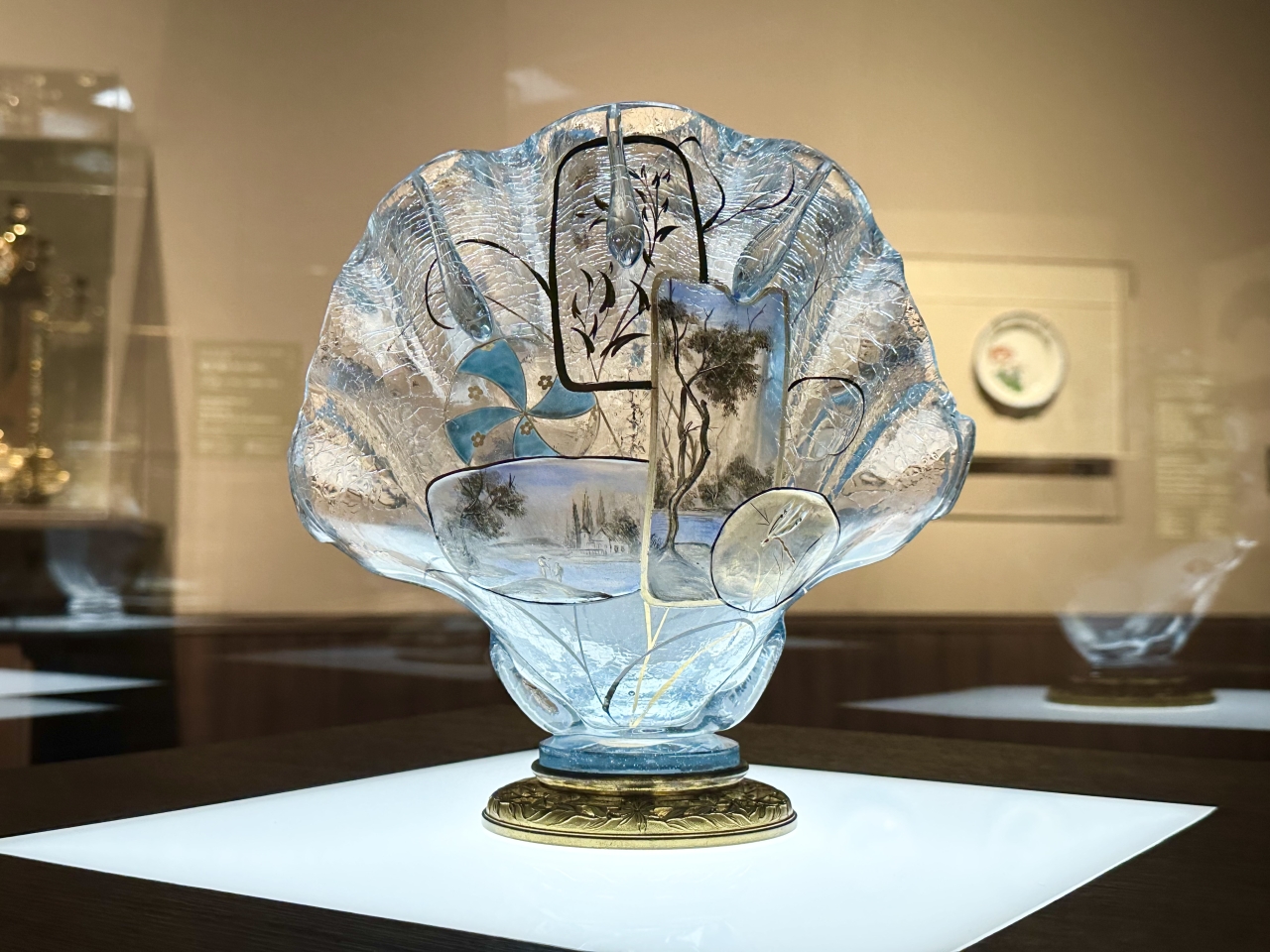

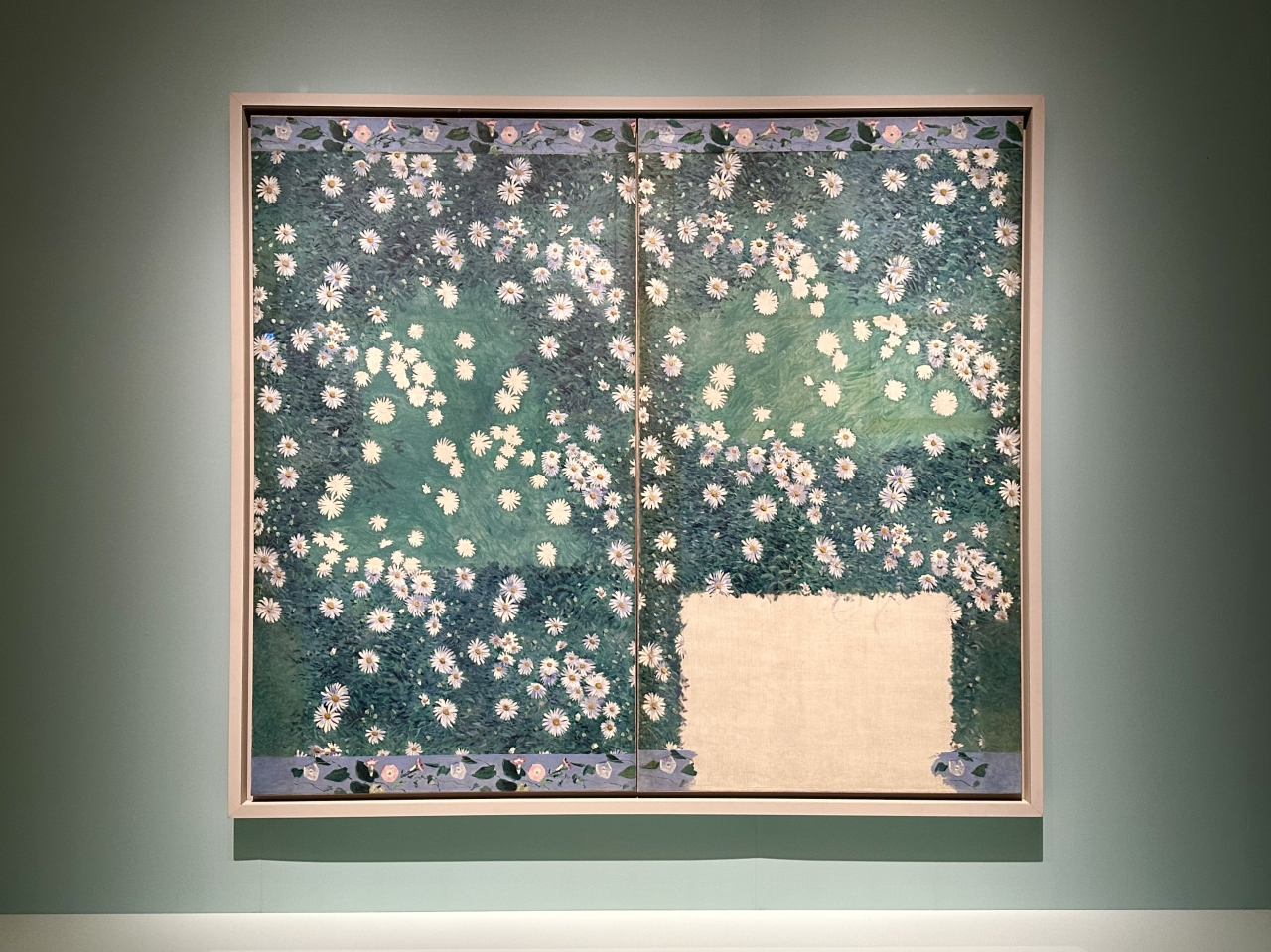

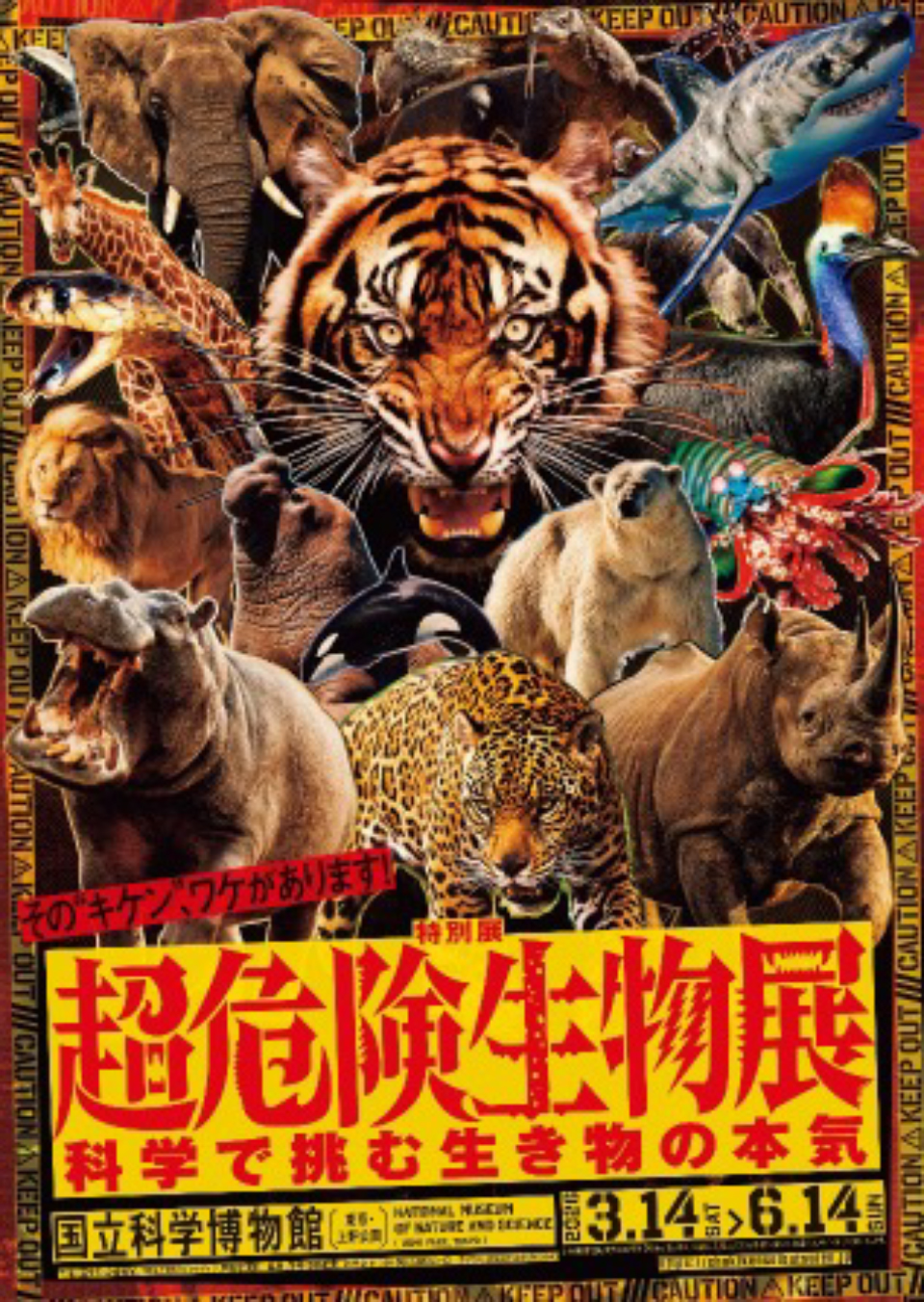

Sweden is a country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in northern Europe. This exhibition is a comprehensive introduction to paintings from the Golden Age of Swedish art, which has been attracting worldwide attention in recent years.

In Sweden, a young generation of artists began studying in France around 1880, and became fascinated with Realism, which portrays humans and nature as they are. When they returned home, they aimed to create art that was uniquely Swedish and reflected the country's identity, portraying nature, the people around them, and the brilliance hidden in everyday life in intimate and emotional expressions.

With the full cooperation of the Nationalmuseum of Sweden, this exhibition explores the uniquely Nordic sensibility of living in harmony with nature through fascinating paintings produced in Sweden from the late 19th century through to the 20th century.

[Event Overview]

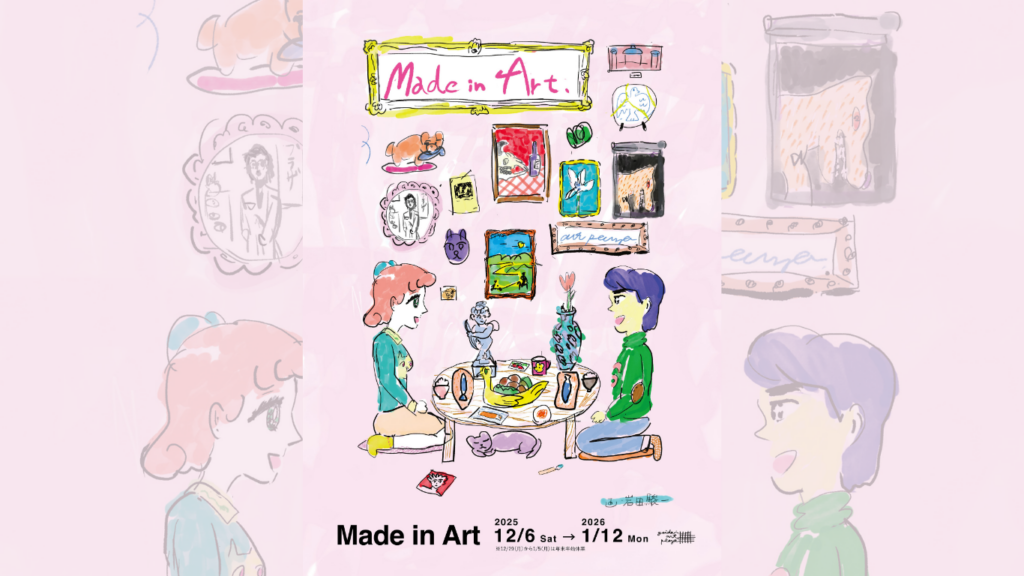

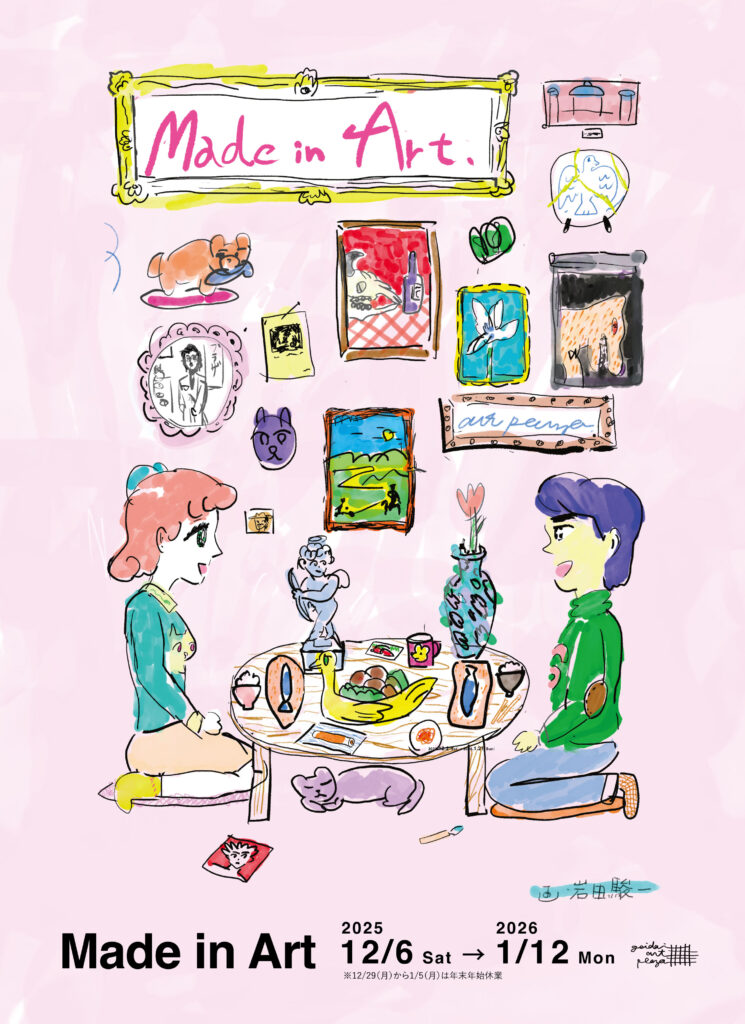

Exhibition title: Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum 100th Anniversary Commemoration: Swedish Paintings: Nordic Light, the Brilliance of Everyday Life

Date: January 27th (Tuesday) – April 12th (Sunday), 2026

Venue: Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, Special Exhibition Room

Closed: Mondays, February 24th (Tuesday) *However, open on February 23rd (Monday, national holiday)

Opening hours: 9:30-17:30, until 20:00 on Fridays (last entry 30 minutes before closing)

Organized by: Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture), NHK, NHK Promotion, Tokyo Shimbun

Sponsored by: DNP Dai Nippon Printing Supported by: Embassy of Sweden Special cooperation: Nationalmuseum of Sweden

Cooperation: All Nippon Airways, Lufthansa Cargo AG Planning cooperation: S2

Admission fee: Tickets will go on sale on Friday, November 28th

Adults: 2,300 yen (2,100 yen), university and vocational school students: 1,300 yen (1,100 yen), those 65 and over: 1,600 yen (1,400 yen)

Free for those under 18 and high school students

*Prices include tax

*Advance ticket prices in parentheses *Free admission for those with a Physical Disability Certificate, Love Certificate, Rehabilitation Certificate, Mental Disability Health and Welfare Certificate, or Atomic Bomb Survivor Health Certificate, and their accompanying person (up to one person)

*Those under 18, high school students, university/vocational school students, those over 65, and those with various certificates must present proof of their age.

*Free admission for university and vocational school students only on weekdays from January 27th (Tue) to February 20th (Fri).

Inquiries: 050-5541-8600 (Hello Dial)

*The session period, opening hours, and closed days may be subject to change.

Please check the official exhibition website for the latest information.

Official exhibition website: https://swedishpainting2026.jp

Exhibition Official X・Instagram: @swedish2026

[Travel information]

Yamaguchi Prefectural Museum of Art: April 28th (Tue) – June 21st (Sun), 2026 (planned)

Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art: Thursday, July 9th – Sunday, October 4th, 2026 (planned)

*This exhibition is part of the Swedish Embassy Year of Cultural and Scientific Cooperation in Japan 2026.

[Swedish Paintings: Nordic Light, Everyday Sparkle Public Relations Office] Press release

See other exhibition information