Tokyo National Museum

To mark the 850th anniversary of the founding of the Jodo sect, a special exhibition titled “Honen and the Pure Land” has begun at the Tokyo National Museum in Ueno, Tokyo, where many treasures related to the founder of the sect, Honen, have been gathered from temples across the country. The exhibition will run until June 9, 2024.

*Some of the artworks on display will be changed during the exhibition. Please check the official exhibition website for details.

Originally developed in India and China, the belief in going to the Pure Land, a world free from suffering established in the west by Amida Buddha, is called “Jodo Buddhism” or “Jodo faith” in Japan and was adopted mainly by the Tendai sect’s Enryakuji Temple on Mount Hiei.

Honen (1133-1212), born at the end of the Heian period, a time when the age of the Latter Day of the Law was plagued by successive wars, natural disasters, and epidemics, studied Pure Land Buddhism on Mount Hiei, and in 1175 (Joan 5) founded the Jodo sect, which taught that by chanting “Namu Amida Butsu,” everyone can be equally saved by Amida Buddha and be reborn in the Pure Land.

“Namu Amida Butsu” means “I take refuge in Amida Tathagata.” The simple teaching of “Senshu Nembutsu,” which says that if you recite this six-character phrase (Nenbutsu) out loud, you will be able to attain paradise regardless of whether you have undergone rigorous training or good deeds, is so simple that it has gained the support of a wide range of people from aristocrats to uneducated commoners who are suffering from hardship, and it has grown into one of the major sects of Kamakura Buddhism. It has been passed down continuously to the present day.

This large-scale exhibition, held to commemorate the 850th anniversary of the founding of the Jodo sect in 2024, will survey the art and history of the Jodo sect, from its founding by Honen to its great development in the Edo period with the support of the Tokugawa Shogunate, through precious treasures, including national treasures and important cultural properties, held by Jodo sect temples and other institutions across the country .

The exhibition is divided into four chapters. Chapter 1, “Honen and His Times,” introduces the kind of person Honen was, his appearance, achievements, and ideas.

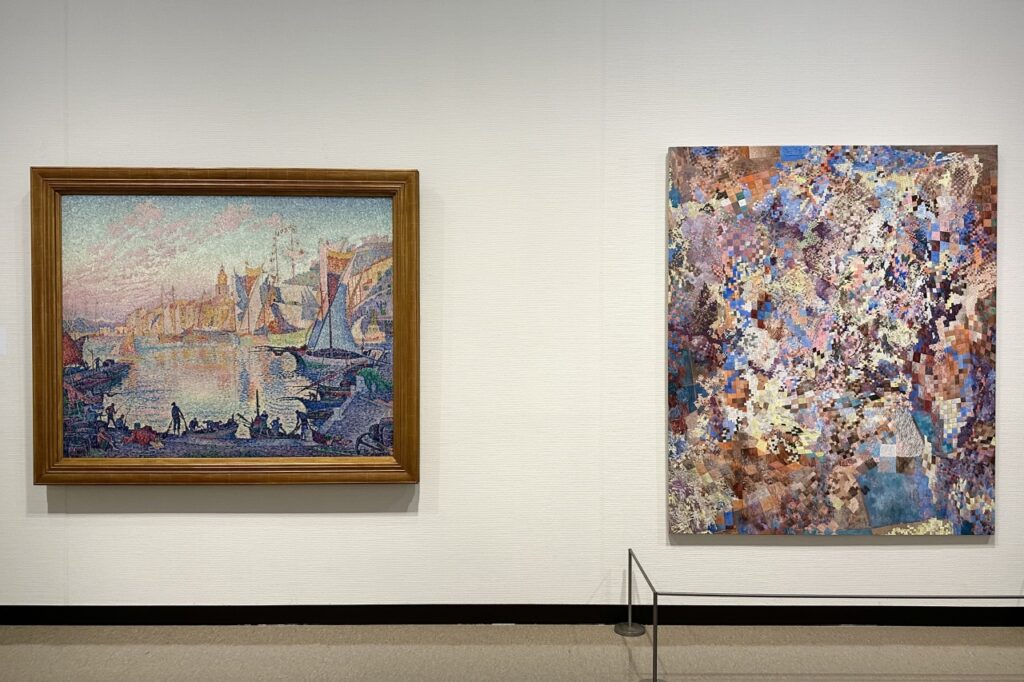

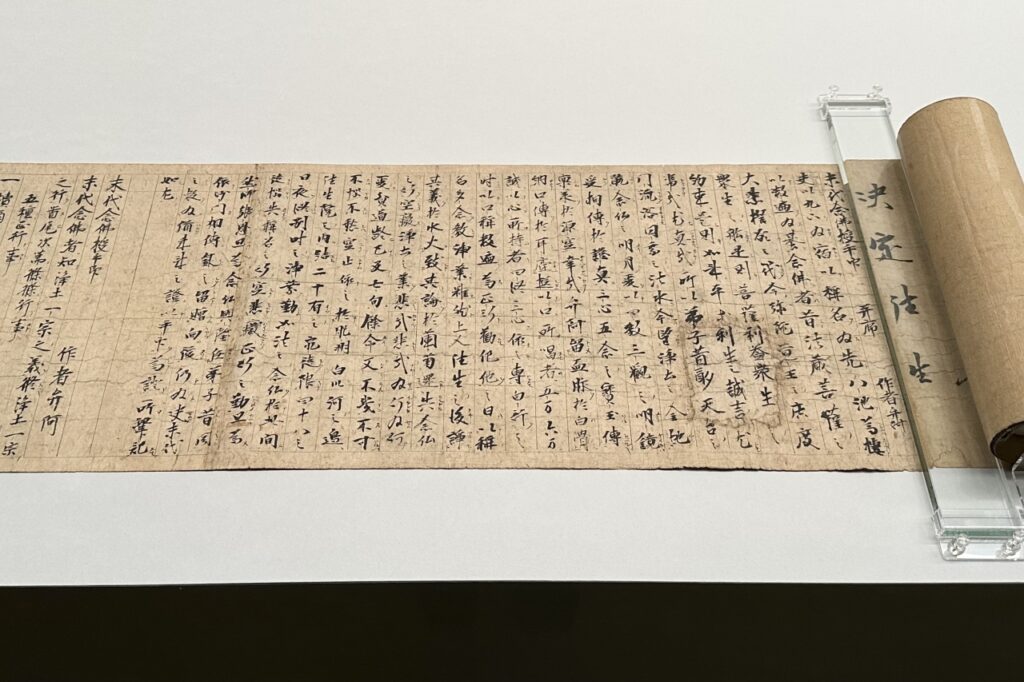

This exhibit features the Important Cultural Property “Senke Hongan Nembutsu Shu (Rosanji version),” which is the fundamental scripture of the Jodo sect that systematizes Honen’s philosophy and whose opening section even features calligraphy written by Honen himself; and the National Treasure “Honen Shonin Illustrated Biography,” a lengthy picture scroll spanning 48 volumes that can be said to be a culmination of the many biographies of Honen, containing not only the life of Honen from his birth to his death, but also the achievements of the nobles, samurai, and disciples who converted to the Jodo sect .

The statue of Saint Honen Seated, the principal image of the Okuin sanctuary of Taimadera Temple in Nara, is a rare example of a sculpture of Honen made in the Middle Ages, and is said to show the figure of a relatively young man. The statue is well-built, with a gentle expression that seems to be slightly smiling. This laid-back friendliness is in keeping with the popularity of the Jodo sect, and it is truly symbolic that it is displayed right at the entrance to this exhibition.

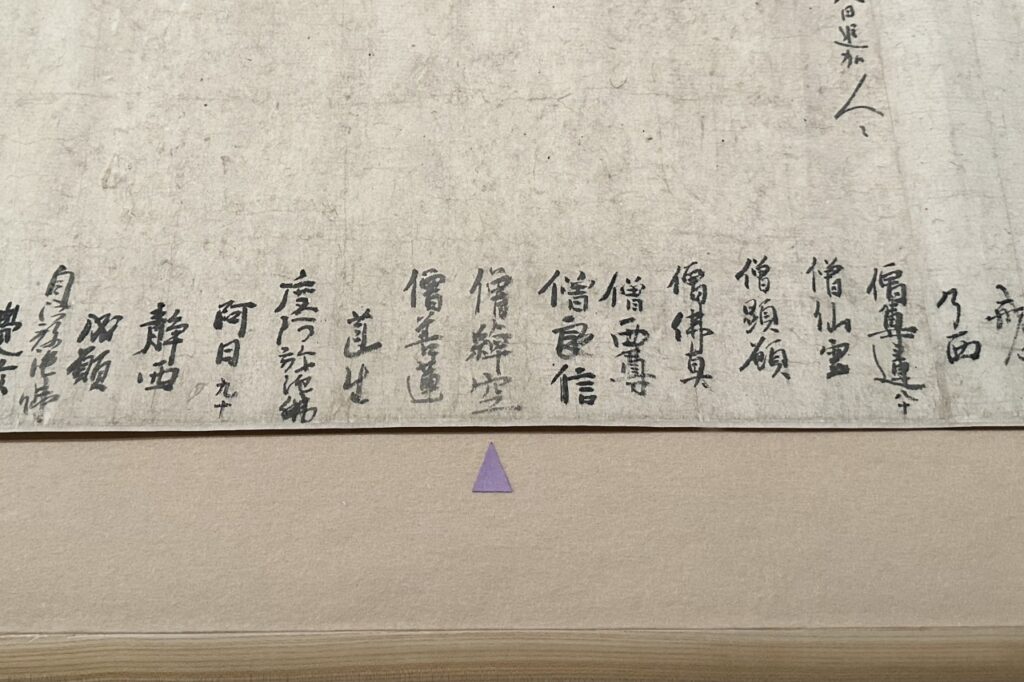

As the influence of the religious organization grew, some of them began to misinterpret the teachings and disrupt public morals, and the followers of Enryaku- ji Temple even filed a lawsuit to demand an end to Senshu Nembutsu. At that time, Honen had his disciples sign the Seven Prohibitions to encourage self-discipline. If you look closely, you will see that it also contains the signature of Shinran, the founder of Jodo Shinshu, when he was young.

The highlight of Chapter 2, “The World of Amida Buddha,” which conveys the growing faith that spread to the common people through the many sculptures of Amida Nyorai that were imbued with the wishes of many people, is the National Treasure “Amida and the Twenty-five Bodhisattvas Raising Welcome,” which is housed in Chion-in Temple in Kyoto, the head temple of the Jodo sect of Buddhism, just like the previously introduced “Illustrated Biography of Honen Shonin.”

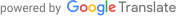

This work is known by the nickname “Hayaraigo” (Early Arrival) , and is featured in textbooks as a masterpiece of Kamakura-period Buddhist painting, so many people should be familiar with it. A Raigo-zu painting is one that depicts Amida Buddha, accompanied by bodhisattvas, descending on a cloud to take a dying person who is reciting the Nembutsu to the Pure Land, and the name “Hayaraigo” comes from the magnificent depiction of flying clouds in a diagonal composition that emphasizes the sense of speed as the water falls in a straight line from the waterfall. This type of design likely reflects the wishes of those who prayed for a swift arrival.

A three-year period beginning in 2019 saw the painting undergo extensive dismantling and repair, which included replacing the backing paper (reinforcing paper that is affixed directly to the back of the original painting), making the painting brighter and enhancing the landscape that gave rise to the three-dimensional expression of scenery that is characteristic of this painting, such as the blue color of the water’s surface and the deeply carved mountain slopes.

The National Treasure “Tsuzureori Taima Mandala,” a treasured principal image of Taima-dera Temple in Nara, a sacred place of Pure Land Buddhism, is also a must-see. This work was originally composed of the third chapter, but due to space constraints, it was displayed in the second chapter area.

This stunning four-meter-wide painting of the Pure Land depicts the contents of the Sutra of Contemplation of Infinite Life, one of the three great scriptures of Pure Land Buddhism. It is thought that the painting was created in China during the Tang Dynasty or in Japan in the 8th century during the Nara period, but there are no other examples from the 8th century created with such advanced techniques. This will be the first time it will be exhibited outside of Nara Prefecture.

Unfortunately, most of the original colors have been lost, but this work attracted great faith during the Kamakura period by Honen’s disciple Shoku, and many copies were made. The same section also exhibits a copy of the Taima Mandala with clearly defined ink lines. Legend has it that the Tapestry Taima Mandala was woven in one night by an aristocratic girl named Chujohime with the help of Amida Buddha using lotus threads, and by viewing it together with the Taima Mandala, you may be able to experience a part of the mysticism that heightened the reverence of the people at the time.

Chapter 3, “Honen’s Disciples and the Lineage of Buddhism,” traces the activities of his disciples who, after his death, worked tirelessly throughout the country, including in Chinzei (Kyushu), Kamakura, and Kyoto, to spread his teachings.

There were many differences in approach among the disciples, such as the ideological construction of Senshu Nembutsu, the positioning of various practices within it, and ensuring the legitimacy of the religious organization. The exhibited work, “Matsudai Nembutsu Jushuin (Seigokurakuhon),” is said to be handwritten by Shoko, the founder of the Chinzei school, and was written to lament the situation in which dissent and different schools of thought were arising among his disciples, and to convey Honen’s true intentions to future generations. It makes you think about how difficult it is to protect and pass on a single teaching, even if it is as simple as Senshu Nembutsu.

Shogei, the founder of the Jodo sect, established the foundations of the Kanto Jodo sect in Hitachi Province, and his disciple Shoso founded Zojoji Temple in Edo. The sect’s status was firmly established when Tokugawa Ieyasu, who had been a devout believer in Jodo Buddhism since the Matsudaira clan, designated Zojoji Temple as the family temple in Edo and Chion-in Temple as the family temple in Kyoto. Chapter 4, “Jodo Buddhism in the Edo Period,” traces the Jodo sect’s dramatic rise in popularity during the Edo period under the patronage of the shogun family and various feudal lords, through the large-scale treasures that were brought to Jodo sect temples.

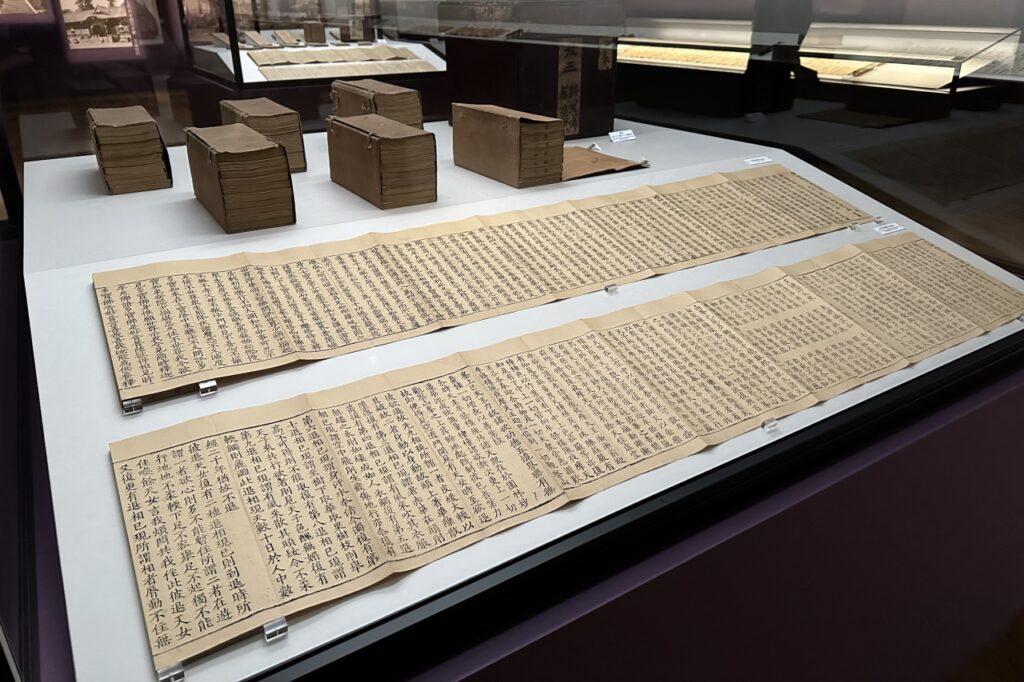

The three copies of the Tripitaka that can be viewed here – Song, Yuan, and Goryeo – are known as the “Three Great Treasures” and were confiscated by Ieyasu from temples in Yamato, Suo, and Omi provinces in exchange for their territories, and donated to Zojoji Temple.

The Tripitaka is a collection of over 5,000 volumes of Buddhist scriptures translated into Chinese, and in China, from the Northern Song Dynasty onwards, the Tripitaka was printed by woodblock printing as printing culture developed. Each published Tripitaka is a rare cultural asset, but it is said that there is no other example in the world of three copies held by a single temple in perfect condition. It is an extremely important book in cultural history that created the foundation for modern Buddhist studies.

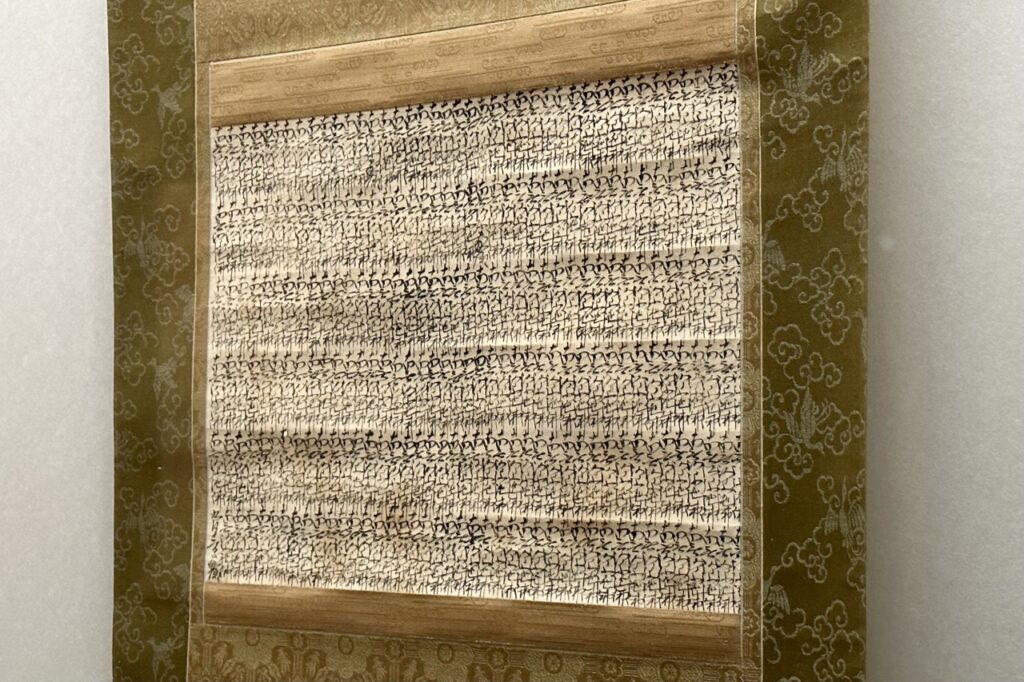

Though not flashy, what caught my eye was the “Daily Nembutsu” (Nenbutsu) that is said to have been written by Ieyasu himself. It is believed that in his later years, Ieyasu diligently copied out the sutra “Namu Amida Butsu” every day, praying for the atonement of his sins. From a distance, the name of Amida Buddha is densely written in six rows and 41 columns, so densely that it could be mistaken for some kind of pattern, and it is a little chilling as it shows just how obsessive he was. However, upon closer inspection, like a game of spot the difference, there are only two places where the characters “Namu Amida Ieyasu” are written instead of “Namu Amida Butsu”. It is unclear why it was written in this way, but perhaps it was just playfulness, or perhaps there was some other deeper intention behind it.

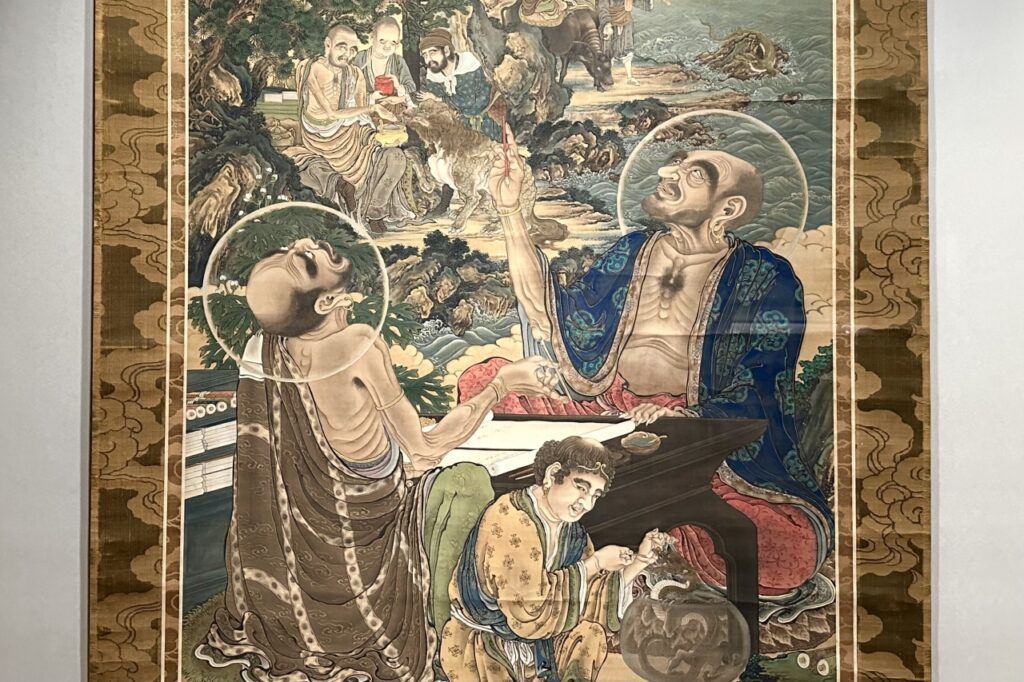

The highlight of this exhibition can be said to be the 500 Arhats from Zojoji Temple , which Kano Kazunobu (1816-63), a painter from the late Edo period who is said to have been largely self-taught before entering the Kano school. The 500 Arhats are a masterpiece that he worked on over a period of about 10 years as the culmination of his career.

Rakan is an honorific title given to enlightened saints among the disciples of Shakyamuni, and they have been worshipped as beings with the role of saving people. The 500 Rakan are the 500 Rakan who participated in the First Assembly to compile Buddhist scriptures after Shakyamuni’s death, and from the mid-Edo period onwards, wood carvings and stone statues of the 500 Rakan began to be actively made all over Japan.

This work is an exceptional piece in terms of size, number, and impact, with 500 arhats literally painted in groups of five across a total of 100 scrolls. The highly distinctive scenes of the arhats’ training and life, the six realms of existence, disasters that befall people, and their salvation through arhat are depicted dramatically in brilliant colors, without being limited by the framework of Japanese painting, and using Western shading and perspective techniques. There is not a single part that is relaxed, even in the four corners, and I was overwhelmed by the amount of information and the passion that comes from it.

Of the total 100 paintings, 24 (12 in the first and second half of the exhibition) will be exhibited at the venue.

The last thing we encounter at the venue is the “Group Statues of Buddha in Nirvana” from Honenji Temple in Kagawa. This work depicts the scene of Shakyamuni’s nirvana in three dimensions using a group of statues, and is made up of a life-size statue of Shakyamuni in Nirvana, surrounded by a total of 82 figures, including lamenting arhats, the Eight Deities of Heavenly Dragons, and animals. Matsudaira Yorishige, the first lord of Takamatsu Domain, invited a Buddhist sculptor from Kyoto to build this work, and there is no other example of such a large group statue of Nirvana.

They are usually placed in the Sanbutsudo (Nirvana Hall) of Honenji Temple, but 26 of them are on display at this exhibition and are open to the public as photo spots.

After Tokyo, the exhibition will travel to the Kyoto National Museum and the Kyushu National Museum.

Overview of “Honen and the Pure Land”

| Dates | Tuesday, April 16th, 2024 – Sunday, June 9th, 2024 |

| venue | Tokyo National Museum Heiseikan |

| Opening hours | 9:30-17:00 (Last admission 30 minutes before closing) |

| closing day | Monday, May 7th (Tuesday) *However, the museum will be open on April 29th (Monday, national holiday) and May 6th (Monday, holiday). |

| Admission fee | Adults: 2,100 yen, University students: 1,300 yen, High school students: 900 yen

*No prior reservations are required for this exhibition. |

| Organizer | Tokyo National Museum, NHK, NHK Promotion, Yomiuri Shimbun |

| inquiry | 050-5541-8600 (Hello Dial) |

| Exhibition official website | https://tsumugu.yomiuri.co.jp/honen2024-25/ |

*The contents of this article are current as of the time of coverage. Please check the official exhibition website for the latest information.