National Museum of Western Art

The exhibition “Naito Collection: Manuscripts – A Microcosm of the Elegant Middle Ages,” which explores the charm of illuminated manuscripts that were popular in medieval Europe, is currently being held at the National Museum of Western Art. The exhibition will run until Sunday, August 25, 2024.

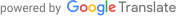

A manuscript is a book that was popular in Europe before the invention of printing technology in the 15th century . It was produced by hand copying text onto vellum, paper made from thin animal skins, and required an enormous amount of time and effort .

Manuscripts were often lavishly decorated and illustrated, and at times became extremely luxurious items; however, they were a major medium of communication for people at the time, and also played an important role in supporting the Christian faith.

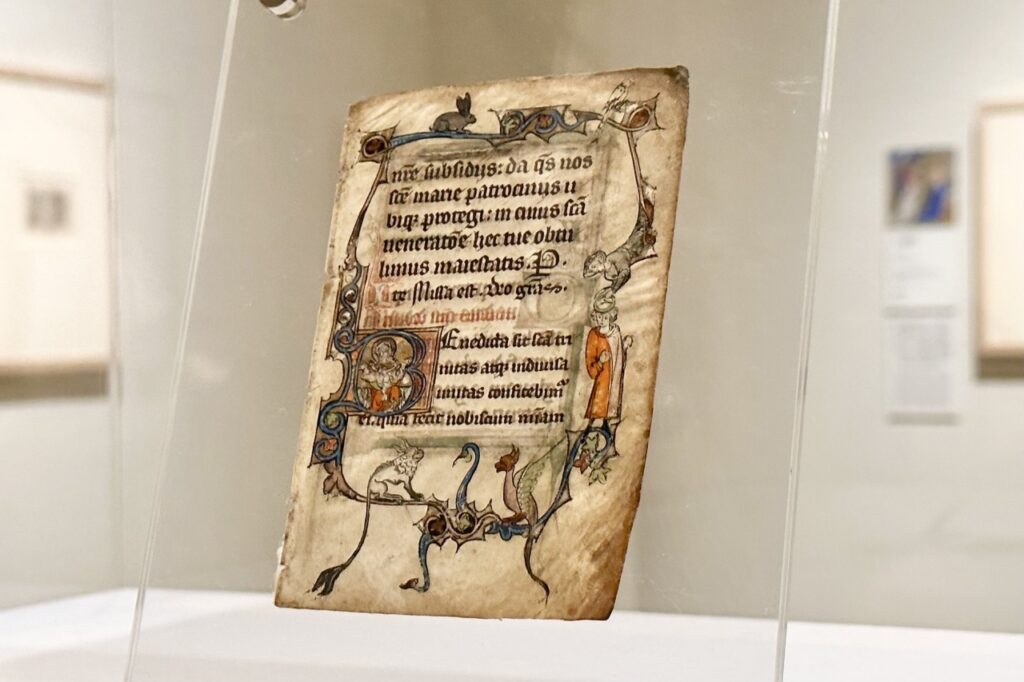

The “Naito Collection” in the title of this exhibition refers to a collection centered on manuscript leaves (individual leaves separated from a book) collected by Hirofumi Naito, professor emeritus at the University of Tsukuba and Ibaraki Prefectural University of Health Sciences. It is one of the largest manuscript collections in a Japanese art museum, and was donated to the museum in 2015, with 26 more manuscript leaves added in 2020.

This large-scale exhibition, featuring approximately 150 items from the majority of the Naito Collection as well as items housed in university libraries around Japan, explores the role of each manuscript and the world of medieval illuminated art*, in which text and pictures are integrated.

(Note: The decoration of manuscripts is called “illuminated” due to its shining, extensive use of gold.)

The exhibition is divided into nine chapters based on the purpose of the parent manuscripts to which the leaves originally belonged: Chapter 1: The Bible, Chapter 2: Psalms, Chapter 3: Manuscripts for the Breviary, Chapter 4: Manuscripts for Mass, Chapter 5: Other manuscripts used by the clergy, Chapter 6: Books of Hours, Chapter 7: Calendars, Chapter 8: Canon Laws and Books of Oaths, and Chapter 9: Secular Manuscripts .

A typical example of manuscript decoration is the initial .

Initials were ornately decorated letters at the beginning of a sentence. They were not only pleasing to the eye, but also served to mark the beginning of important sections of the text or to separate clauses. What’s interesting is that the type of decoration could indicate the hierarchy of the initial, and therefore of the text.

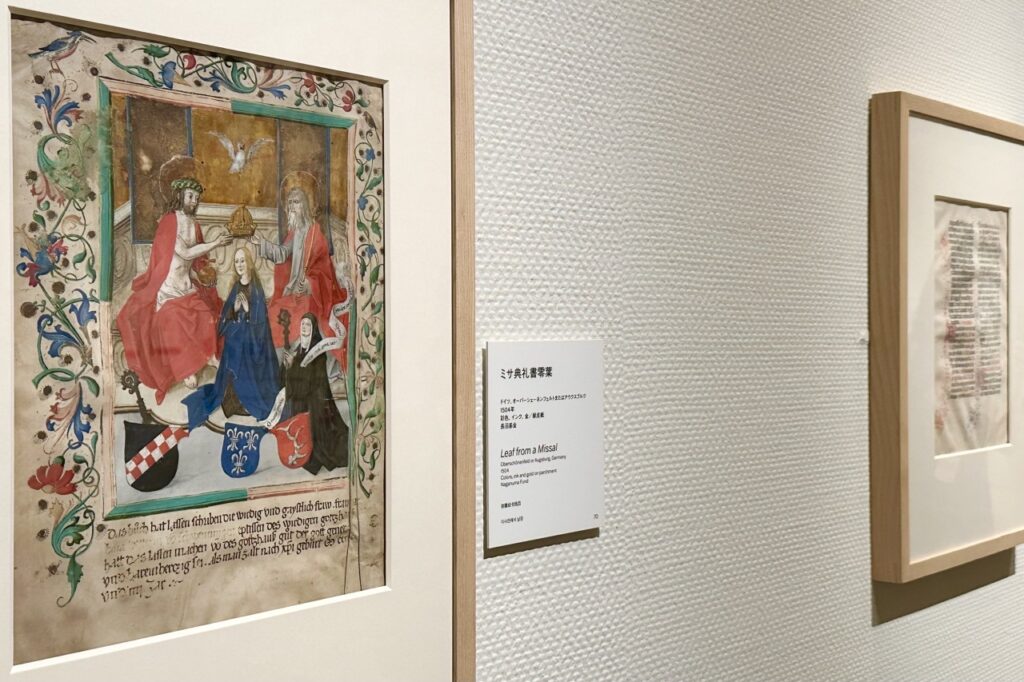

For example, in the center left of the page of the “Liturgical Psalm Leaf” there is a large letter “B”, and in the upper part of the “B” there is a figure of God blessing, and in the lower part there is a figure of David, the traditional author of the “Psalm”, playing an instrument. In this way, a depiction of a story scene or person in the space inside the letter is called a “narrative initial”.

There are other types of initials, such as “champagne initials” with gold letters on a colored background and “filigree initials” with lines around the letters, but in terms of hierarchy, narrative initials are at the top. By showing the core text with the most prominent narrative initials, they visually assisted the reader in understanding the text.

The Liturgical Psalms are a compilation of the texts of the Psalms from the Old Testament, as well as hymns and prayers, for the Divine Office , a worship service held at set times eight times a day in monasteries and churches.

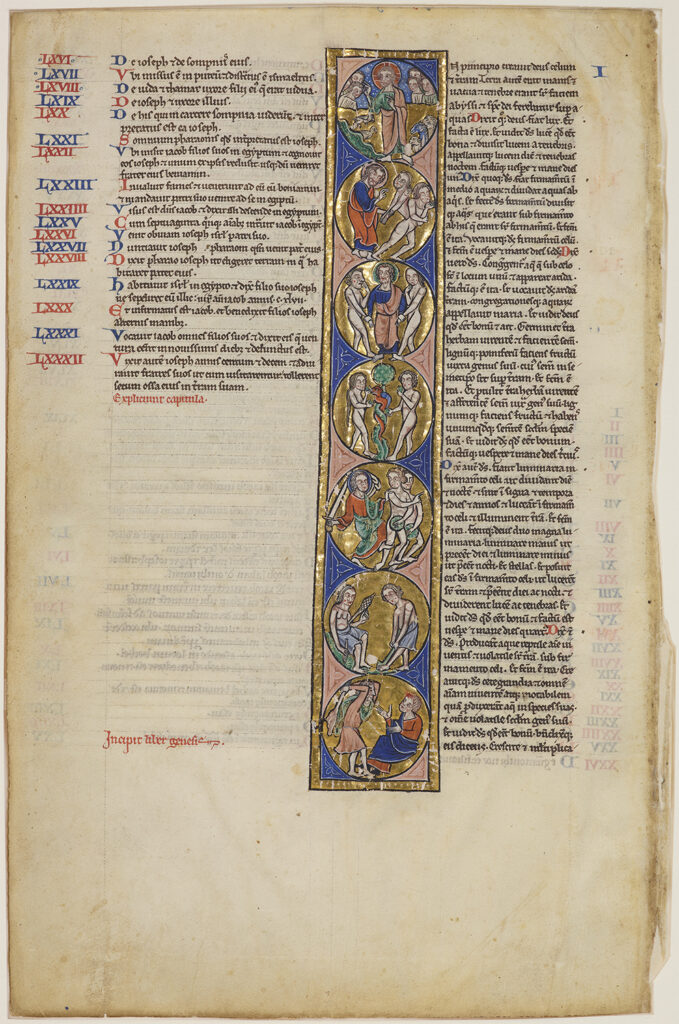

The Naito Collection contains many leaves from Bible manuscripts produced in 13th century England and France, and the Bible Leaf showing the beginning of Genesis is a representative example of this.

Among the densely packed, detailed layout of a huge number of characters, the gold-bordered decoration that runs vertically across the page catches your eye, but you’ll be surprised to find out that it’s actually a giant “I” for the story. It’s a scale befitting the beginning of a grand story. In a small circle of just 2cm in size, it intricately depicts the story from God’s creation of all things to Cain’s murder of Abel.

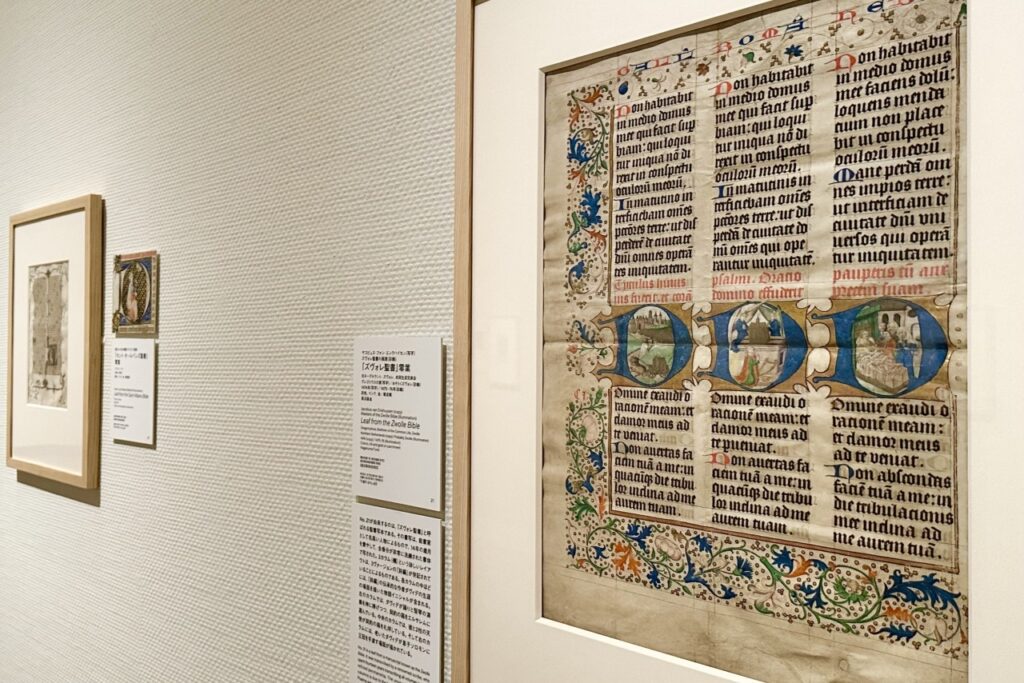

Leaf of the Zwolle Bible, produced in the late 15th century in the town of Zwolle in the North Netherland (near present-day Netherlands), is a leaf that emphasizes the letter “D” including the initial of the story. I was captivated by its neat and tidy beauty.

Initially, monks and nuns were responsible for copying and illuminating the manuscripts, but gradually lay artisans began to join in. The refined typeface seen in this work, which looks almost impossible to have been handwritten, was created by the renowned calligrapher Jacobus van Enkhuisen, who is said to have spent 14 years copying the entire volume.

This harmonious layout is the result of juxtaposing three versions of the Psalms, each with a narrative initial depicting a scene from David’s life, such as David carrying the Ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem.

In some cases, initials indicate for whom the manuscript was produced and the occasion for which it was used, for example, the initial “C” on the Liturgical Poems Leaf depicts a Franciscan friar singing in front of a lectern, indicating that the original manuscript was produced for the Franciscan Order.

Incidentally, border decorations that use plant motifs to fill the margins of the pages, as in this work, are common among manuscripts, but on closer inspection this work is quite unique in that, among the graceful, vividly colored flowers and plants, there is the head of a strange old man, perhaps a monk.

There were also other leaves at the venue with mischievous-looking decorations in the margins, perhaps as a sign of the artist’s playfulness, and it was fun to check out every page.

The Breviary, which contains all the texts to be read during the Divine Office, was originally kept by the priest who conducted the service, but gradually became popular among ordinary believers as well.

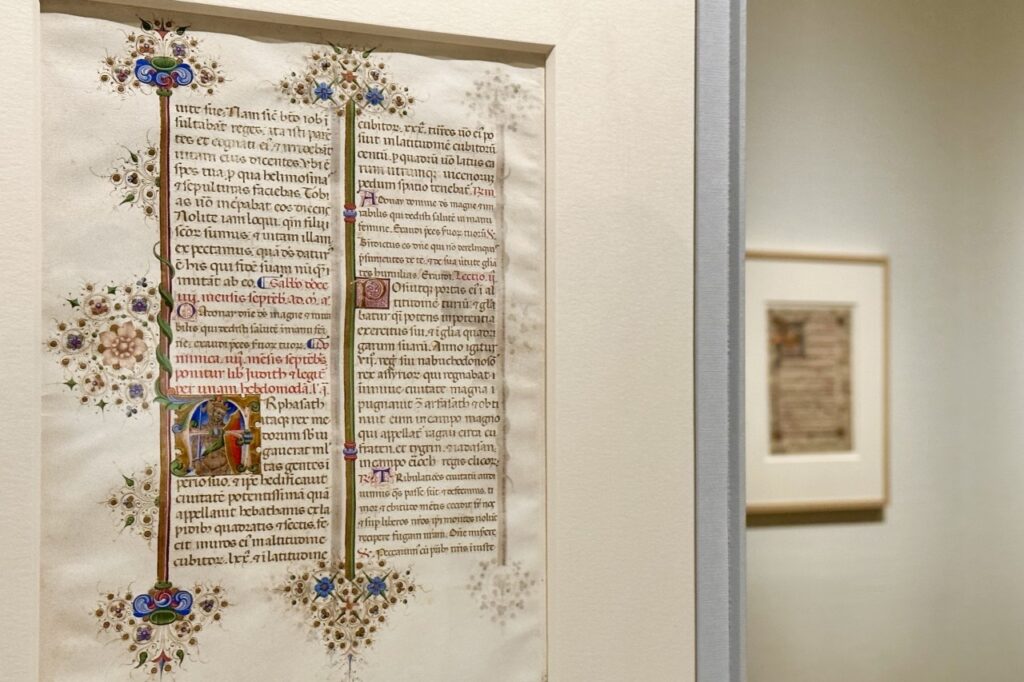

Among them, the leaf of the “Breviary of Leonello d’Este”, commissioned by the Este family who ruled the Italian city of Ferrara in the 15th century, is a gorgeous example of the utmost luxury for secular believers. The frame decoration, with its gold studded and fine lines like threads, is reminiscent of the sparkle of lavish jewelry and is nothing short of magnificent.

The decoration was done by Giorgio D’Alemagna, one of Ferrara’s leading manuscript illuminators, and although the overall style is late Gothic, the Renaissance was already underway in Ferrara at the time, and the way the figures are depicted within the initials shows some Renaissance influence.

Because manuscript decorations have been preserved within books and have avoided scattering and damage compared to murals and tapestries, they can be considered valuable witnesses to medieval art. This work, too, is a good example of a period in which the essence of two aesthetic sensibilities at the time of the transition in fashion is sealed away.

Of course, there are also many Zeroyo leaves that, rather than being decorated with initials, feature miniatures (illustrations) that are assigned their own independent space on the page.

The Prayer Book Leaf features an illustration of Christ surrounded by a trompe l’oeil-style decoration of flowers and insects scattered on a gold background (a type of optical illusion that was popular in Ghent and Bruges around 1500). The leaf was originally produced to be inserted into an existing manuscript to enhance its aesthetic value, but the owner added an embroidered border to it and used it in worship in the form of a small painting.

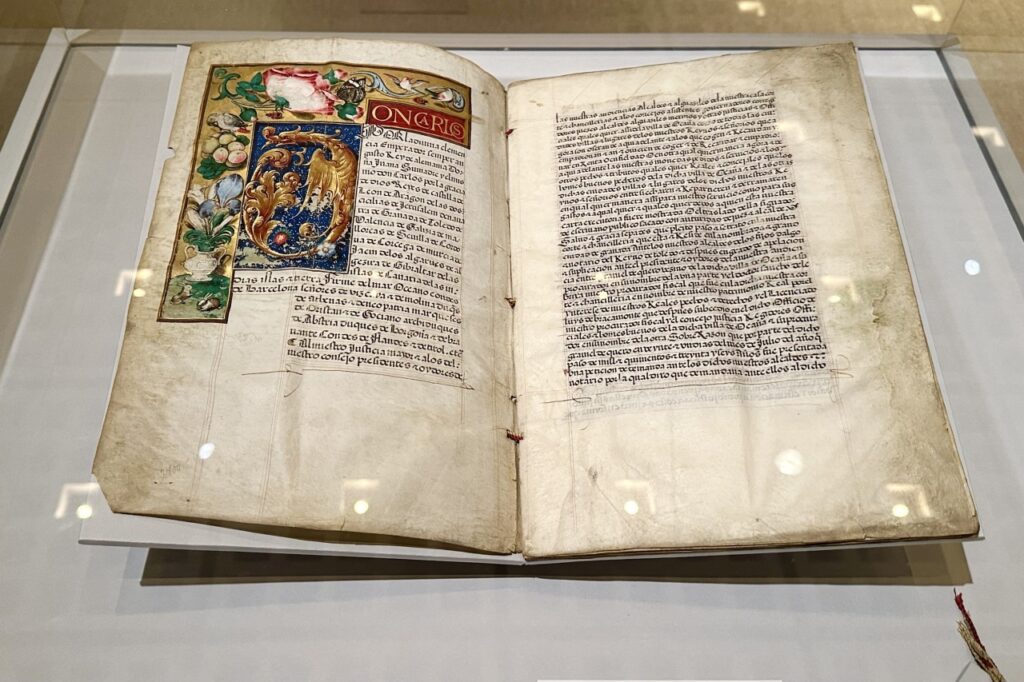

The exhibition also included non-Christian “secular” manuscripts, such as encyclopedic works and identity cards. As a result of the research, the exhibition also featured parent manuscripts of the zero leaf, which were identified based on the content of the copied text, the typeface, and the style of decoration, as well as sister leaves that had been separated from the parent.

Illuminated manuscripts were sometimes used as status symbols for their owners, or were lavishly decorated to satisfy aesthetic tastes. Some collectors cut out only the decorative parts, and they were cherished as first-class works of art that went beyond the realm of books. Although many of them are small in size, they are infused with the same aesthetic sense as the Western paintings we usually see in museums, and are in no way less impressive. Why not visit this exhibition and reflect on the aesthetic sense of the people of the Middle Ages, who probably read books with a different sensibility than we do today?

Summary of “Naito Collection Manuscripts – A Microcosm of the Elegant Middle Ages”

| Dates | June 11, 2024 (Tuesday) – August 25, 2024 (Sunday) |

| venue | National Museum of Western Art, Special Exhibition Room |

| Opening hours | 9:30-17:30 (9:30-20:00 on Fridays and Saturdays) *Last admission is 30 minutes before closing. |

| closing day | Monday, July 16th (Tuesday) However, the museum will be open on July 15th (Monday, national holiday), August 12th (Monday, holiday), and August 13th (Tuesday). |

| Admission fee | Adults: 1,700 yen, university students: 1,300 yen, high school students: 1,000 yen

*Free for junior high school students and younger. |

| Organizer | National Museum of Western Art, The Asahi Shimbun Company |

| inquiry | 050-5541-8600 (Hello Dial) |

| Official exhibition page | https://www.nmwa.go.jp/jp/exhibitions/2024manuscript.html |

*The contents of this article are current as of the time of coverage. Please check the official exhibition website for the latest information.