National Museum of Western Art

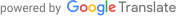

The exhibition “Monet: Water Lilies” has opened at the National Museum of Western Art in Ueno, Tokyo, focusing on the late works of Claude Monet, a representative Impressionist painter, and the changes in his expression. The exhibition will run until February 11, 2025.

Claude Monet (1840-1926) is also known for establishing the technique of “series painting,” in which he observes the same motif in different seasons and weather conditions, and captures the ever-changing impressions and movement of light on multiple canvases. In 1890, at the age of 50, Monet purchased land and a house in the small village of Giverny, France, and spent several years creating a “water garden” with a water lily pond. The surface of this water lily pond, where the surrounding trees, sky, and light are reflected together, became Monet’s greatest creative source in his later years.

This exhibition will introduce Monet’s artistic expression from his later years, which constitutes the culmination of his career, focusing on his Water Lilies series, from his earliest and precious Water Lilies to large-scale Water Lilies created during the process of creating the “large decorative paintings” that occupied his mind until the end.

The exhibition will bring 48 paintings, including 7 that will be shown in Japan for the first time, from the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris, which boasts one of the world’s largest collections of Monet paintings. A total of 66 works will be on display, including masterpieces from the Matsukata Collection at the National Museum of Western Art and other collections in Japan.

A large blown-up photograph at the entrance to the venue shows Monet’s hatted head reflected in a water lily pond. Sylvie Carlier, head of collections and chief curator of cultural properties at the Marmottan Monet Museum, who attended the press preview of the exhibition, said, “The photograph visually conveys the overall intention of the exhibition, which is to move together with Monet through the waterscape and the plants that live near it, through Monet’s perspective.”

This exhibition is composed of four chapters and an epilogue. Chapter 1, “From the Seine to the Water Lilies,” introduces works depicting London and the Seine, which were Monet’s main creative sources in the late 1890s before he began working on Water Lilies. It shows how Monet became interested in the motif of water and the effects of light and reflections on the water’s surface.

In addition, it is said that Monet first painted “Water Lilies” in 1897, and Chapter 1 also exhibits valuable examples that are believed to be the earliest “Water Lilies” .

In contrast to his later series, he focuses on the water lilies themselves rather than the water surface reflecting the trees and sky. The forms of the objects are depicted with meticulous brushwork while retaining realistic elements, allowing for comparison with his later increasingly abstract works.

Decorative arts flourished in France at the end of the 19th century like never before, and Monet also began to create full-scale decorative paintings during the Impressionist period of the 1870s. In the 1890s, while pursuing the effect of exhibiting a series of works, he came up with the idea of “Grande Décoration,” a series of decorative paintings that would fill the exhibition space with a single theme: water lilies. Despite suffering from cataracts, he began working on this energetically from 1914, and it eventually came to fruition in the form of eight huge decorative panels that covered the entire exhibition room of the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris.

Although the final motif was water, water lilies, and willow trees, Monet’s original plan was to incorporate a wide variety of flowers planted around the pond, as he was a great horticulture enthusiast . Chapter 2, “Decoration of Water and Flowers,” features works that were an important part of the concept, such as the wisteria creeping on the arched bridge over the pond and the agapanthus blooming on the shore.

Irises were one of Monet’s favorite flowers, and of the flower studies he created after 1914, he painted irises in the most number of works, second only to water lilies, totaling 20. At first glance, Yellow Irises seems to be a composition looking up at the irises from the perspective of an insect or fish, but in fact it combines two different perspectives: the irises captured from the side, and a viewer looking down at the surface of the pond on which the sky is reflected. Monet was intent on exploring pictorial spaces that would shake up the viewer’s perceptions.

Chapter 3, “The Path to Large Decorative Paintings,” displays nine large works that are particularly related to the finished form of the “Water Lilies” created during the production process of the large decorative paintings. This is the highlight of the exhibition, where you can be surrounded by “Water Lilies” in an elliptical exhibition space inspired by the exhibition room of the Musée de l’Orangerie, and become one with the world of meditative colors that stretches out endlessly. In addition, photography is also allowed in this area.

In two of the nine works, the reflection of clouds, which became an important motif in his work after 1914, is prominent. In the other, white clouds tinted faintly orange are at the center, creating a clear contrast with the blue sky. Water lilies and weeping willows painted with free-spirited brushstrokes stretch out above, below, left and right of the picture, giving a lively impression.

One view is that Monet began to place importance on the reflection of clouds because he wanted to strengthen the sense that heaven and earth are one on the surface of the pond, by combining them with elements connected to the earth, such as poplars and willow trees.

The production of these huge decorative panels was based on studies that Monet had painted outdoors in his newly constructed, vast studio. Through the process of internalizing the memory of impressions of nature and reconstructing them on canvas, Monet’s art became detached from the reality reflected on the retina and transformed into more internal images.

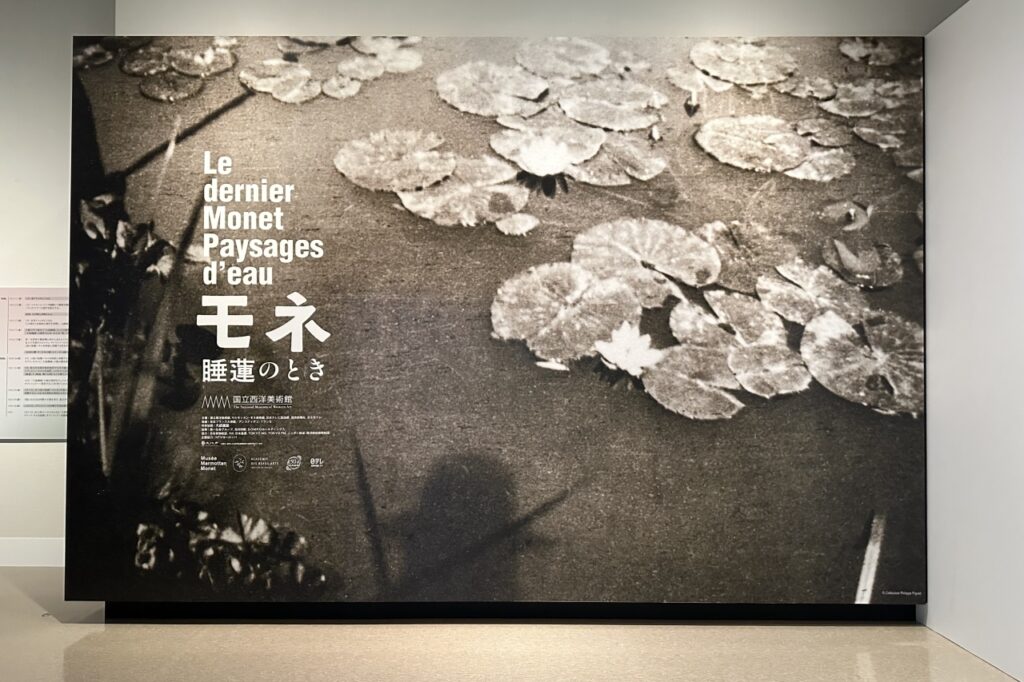

Chapter 4, “Symphonic Colors,” introduces a series of small works that were created in parallel with the large decorative paintings that he continued until his death. The motifs include a Japanese-style drum bridge over a water lily pond and a path with a rose arch in the “Flower Garden” adjacent to the “Water Garden.”

Perhaps due to his deteriorating eyesight caused by his progressive cataracts, his works gradually lost their sense of perspective and began to take on a flat expanse. His color vision also became distorted; at times yellow and green dominated his world, and at other times all other colors seemed bluish, with reds in particular appearing muddy. After undergoing three surgeries from 1923, his eyesight recovered to some extent, but the “Japanese Bridges” series, which he painted during that time, show a tangle of colors so tangled that the motifs are indistinguishable, the outlines melt, and the brushstrokes are densely intertwined.

Looking back at the delicate expressions seen in Chapter 1, you will be surprised at the clear difference. The way he persistently applies color, slamming his brush down, seems to imprint the reality of the motif, but it also feels like an expression of his fear of the disabilities that could be fatal to a painter, such as declining eyesight and a lack of color.

However, Monet actually kept these series of paintings from his final years, which at first glance could be seen as the product of a period of uncertainty, until the very end. Considering that he was a perfectionist who ruthlessly discarded anything he didn’t like, we can see them as the fruit of a rich experimental spirit based on the sense of color he had cultivated through his experiences.

The epilogue, “An Upside-Down World,” concludes the exhibition with two works depicting weeping willows, created as studies for large decorative paintings. In the last years of Monet’s life, when he faced many hardships, including the death of his beloved family and the First World War, these weeping willows are also interpreted as motifs symbolizing sadness and mourning, as they appear to be shedding tears.

In conceiving his large decorative paintings, Monet aimed to create a space where the viewer could be enveloped in an infinite expanse of water with no beginning or end, and could meditate peacefully. In this Water Lilies , the boundary between the real and virtual images of the weeping willows that occupy the left half of the painting is extremely ambiguous, giving the viewer the impression of a tranquil and eternal world.

In his later years, Monet overturned the worldview based on the traditional perspective of Western painting with a new way of perceiving space. Don’t miss the exhibition “Monet: The Time of Water Lilies,” where you can experience the rich development of his artistic career, which went beyond Impressionism with his unabated creative impulse.

Overview of “Monet’s Water Lilies”

| Dates | October 5, 2024 [Sat] – February 11, 2025 [Tuesday/Holiday] |

| venue | National Museum of Western Art (Ueno Park, Tokyo) |

| Opening hours | 9:30 – 17:30 (until 21:00 on Fridays and Saturdays) *Last admission is 30 minutes before closing. |

| Closed Days | Mondays, November 5 (Tuesday), December 28 (Saturday) – January 1, 2025 (Wednesday, national holiday), January 14 (Tuesday) (However, the museum will be open on November 4 (Monday, holiday), January 13, 2025 (Monday, holiday), February 10 (Monday), and February 11 (Tuesday, holiday)) |

| Admission fee (tax included) | Adults: 2,300 yen, University students: 1,400 yen, High school students: 1,000 yen

* Free for junior high school students and younger, people with physical or mental disabilities, and one accompanying person. For further details, please see the official exhibition website. |

| Organizer | National Museum of Western Art, Marmottan Monet Museum, Nippon Television Network Corporation, The Yomiuri Shimbun, BS Nippon Television |

| inquiry | 050-5541-8600 (Hello Dial) |

| Exhibition official website | https://www.ntv.co.jp/monet2024/ |

*The contents of this article are current as of the time of coverage. Please check the official exhibition website for the latest information.