National Museum of Western Art

The National Museum of Western Art is hosting an exhibition titled “Impressionism from the Musée d’Orsay: Stories of Interiors,” which focuses on the representations of interiors by Impressionist painters. The exhibition will run from Saturday, October 25, 2025 to Sunday, February 15, 2026.

When we hear the word “Impressionism,” the first thing that comes to mind is probably landscape paintings that capture outdoor light or the changing atmosphere. Their approach to creating landscapes and their use of plein air certainly brought about a revolution in modern art. At the same time, an interest in interior space was also an essential aspect of Impressionism, as exemplified by Edgar Degas, who explored the effects of artificial lighting rather than natural light and left behind many masterpieces of interior paintings based on refined human observation.

The first Impressionist exhibition was held in Paris in 1874, a time when the city was rapidly modernizing after undergoing extensive urban development projects, known as the Haussmann Reformation. In this bustling and vibrant metropolis, indoor scenes, where people spent much of their time, were more intimate than outdoors and could be said to be an essentially modern subject. In other words, they provided the perfect subject to inspire artists seeking to create new paintings that were in tune with the times.

This exhibition will feature approximately 100 paintings, drawings, and decorative arts, including around 70 masterpieces from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, known as the “Temple of Impressionism,” as well as important works from Japan and abroad . The exhibition will explore the interests and expressive challenges of the interiors of Impressionist and contemporaries painters such as Degas, Manet, Monet, and Renoir in four chapters.

Chapter 1, “Portraits in Interiors,” focuses on portraiture, which was extremely popular in salons and the art market in the late 19th century and was an important means of expression for the Impressionists. In their portraits, they depicted models in their everyday environments, attempting to express social attributes such as their personality, occupation, social class, and aesthetic tastes, sometimes interweaving them with careful direction.

The highlight of this section is Degas’s masterpiece from his youth , “Family Portrait (The Berelli Family)” (1858-69), which has been restored and is now on display in Japan for the first time. Degas’s aunt and her family, who were in exile in Florence, appear at first glance to be a formal family portrait, set in a room in a typically bourgeois, custom-built apartment, adorned with a striking blue hue. However, the work not only frankly captures the personalities and individuality of each individual, but also suggests the couple’s tense relationship and the psychological distance between them through skillful manipulation of facial expressions, poses, and positioning, like a psychological drama. This approach, which departs from the conventional, superficially idealized image of the family, is strikingly modern, and the young Degas’s sincerity and keen, keen observational eye are evident.

The poetic Corner of an Apartment (1875), depicting Monet’s home in Argenteuil near Paris, is one of his few interior paintings. Monet’s keen sense of light effects is fully displayed, with the open curtains and plants in the foreground and the dimly lit room beyond creating a dramatic contrast of light and shadow, warm and cool colors. The figures of his son Jean and a woman believed to be his wife, Camille, are depicted very subtly, almost as silhouettes, but the repeated diagonal lines on the curtains and parquet floor guide the eye and emphasize their impact.

In the second half of the 19th century, when clear boundaries were being drawn between the workplace and the home, in contrast to men who roamed public spaces, women of the bourgeoisie, who were not permitted to go out freely, mainly focused their activities within the home. Chapter 2, “Scenes of Everyday Life,” introduces works that capture casual scenes of women enjoying their hobbies and handicrafts in the comfort of their homes, such as musical recitals, reading, and needlework.

Renoir’s Girls Playing the Piano (1892), which is also used as the main visual for this exhibition, was created at the request of the Director General of the Fine Arts Bureau at the time, with the expectation that the work would be purchased by the Musée du Luxembourg (then the National Museum of Modern Art). At the time, owning a piano signified wealth and a cultured lifestyle, and playing the piano was a hobby enjoyed by the daughters of the upper class, making it a popular subject for painting. This work, with its dazzling composition of warm colors and soft brushstrokes, depicts girls with their faces close together, peering at sheet music, as an ideal image of a bourgeois family.

Chapter 3, “Outdoor Light and Nature Indoors,” showcases how the Impressionists incorporated their interest in outdoor light and nature into their work, featuring works set in complex spaces that connect the indoor and outdoor spaces, such as balconies, terraces, and greenhouses, which were popular social spaces in the 19th century.

Albert Bartolome’s In the Greenhouse (c. 1881) depicts a scene in a glass greenhouse custom-built for his home. Leaving the strong sunlight behind, Bartolome’s wife, Prosperi, dressed in a cool purple summer dress, steps into the dim light of the greenhouse, where palm trees and geraniums are sprouting vibrant leaves. The soft light that casts irregular shadows on her face and dress creates a comfortable summer atmosphere.

Shortly after this work was painted, Prosperi fell ill and passed away in 1887. Bartholomew, overcome with grief, treasured the memory of the glorious day captured in this work, and apparently never let go of either the painting or the dress. As a special touch, the actual dress has been displayed alongside the painting at the exhibition.

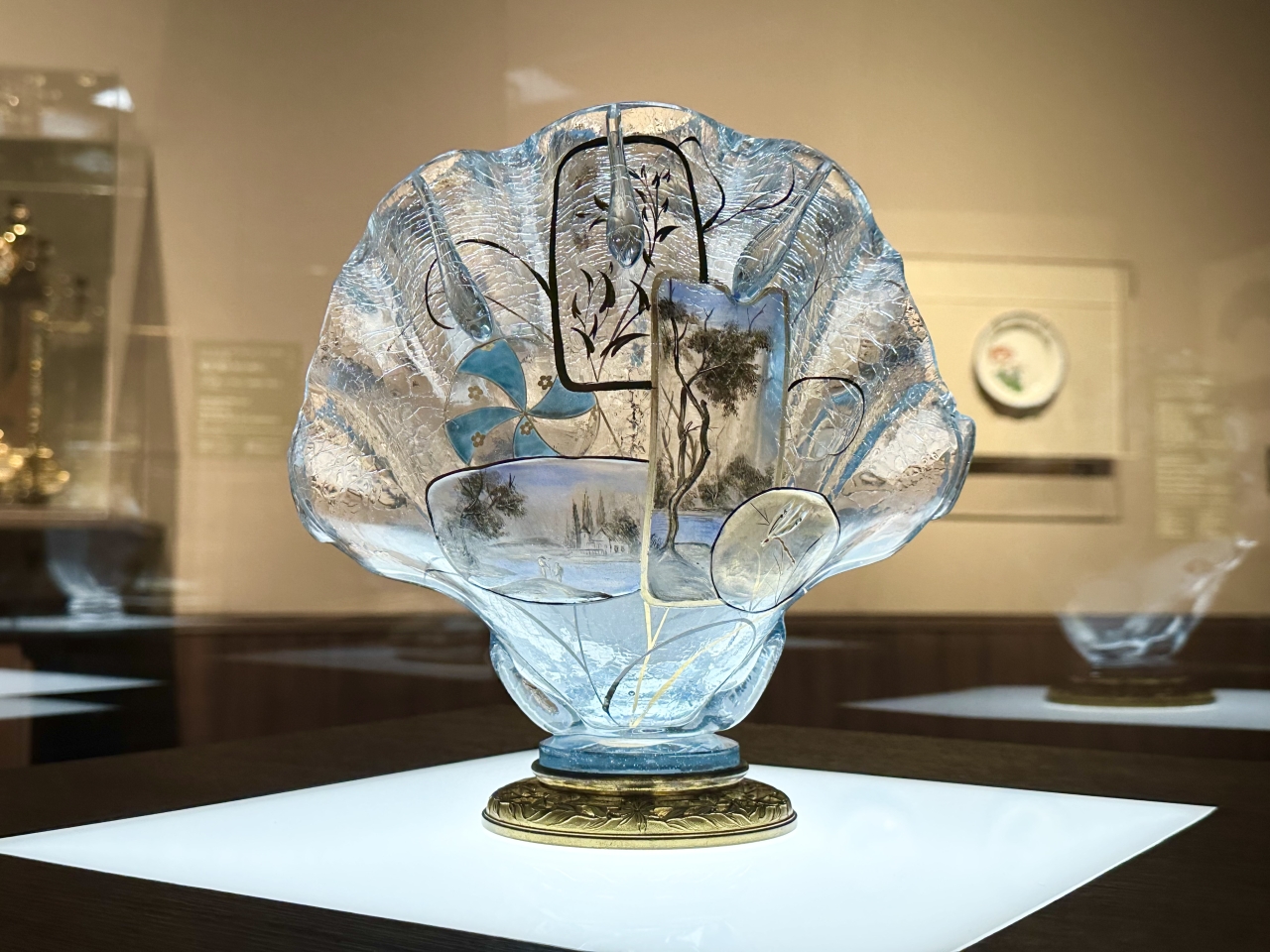

The chapter also introduces still life paintings that presented nature as a decorative element brought indoors, and the development of Japonism, which used nature as its primary source of inspiration to create innovative decorative art.

Chapter 4, “Impressionist Decoration,” examines the various interior decorative representations that emerged as the Impressionists incorporated nature into the interior, at a time when decorative art, which had previously been considered a low-class and superficial form of expression, was increasingly viewed positively. Examinations include a mansion design for the Romanian aristocrat Prince Bibesco, a collaboration between the young Renoir and architect Charles-Justin Le Cour, and a model of Morisot’s own drawing room and studio, providing a glimpse of the effect that decorative paintings added to living spaces.

Manet and Monet created paintings to decorate the château owned by their patron, the businessman Ernest Hoschedé. Manet’s Child Among Flowers (Jacques Hoschedé) (1876) depicts the Hoschedé family’s eldest son, Jacques, peeking out from the flowers growing in the garden, while Monet’s Turkeys (1877) depicts a flock of poultry strolling across a meadow with the château in the background. Both paintings capture scenes and motifs familiar to the Hoschedé family with the bright colors and bold brushstrokes typical of Impressionism, allowing us to enjoy the aesthetics of Impressionism as well as the tastes of their clients.

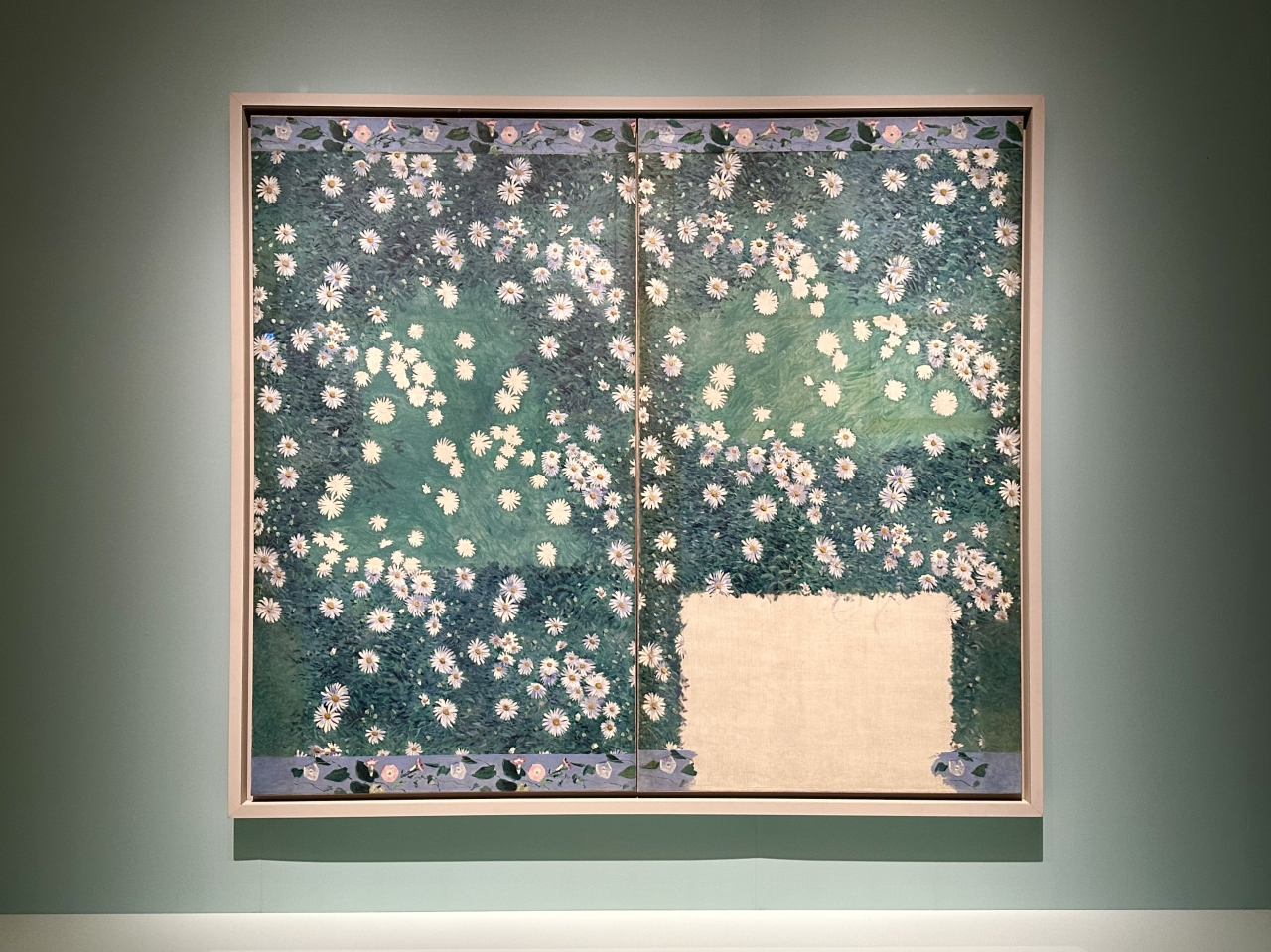

Gustave Caillebotte, who shared Monet’s passion for horticulture and landscaping, also had a strong interest in decorative botanical paintings. Bed of Daisies (1892-1893) is an unfinished work that is thought to have been conceived as a wall decoration for his own home. By scattering white daisies across the canvas from a bird’s-eye view, the work creates a sense of immersion that seems to envelop the viewer. The image, which stretches out infinitely without beginning or end, overlaps with the Water Lilies series that culminated in Monet’s “Large Decorative Paintings” project.

The exhibition “Impressionism from the Musée d’Orsay – A Tale of the Interior” allows visitors to experience the charm of Impressionism, which created innovative art that transcended the boundaries between nature and the interior amid urban life in 19th century Paris. The exhibition will run until Sunday, February 15, 2026.

Overview of “Impressionism from the Musée d’Orsay: A Tale of Interiors”

| Dates | Saturday, October 25, 2025 – Sunday, February 15, 2026 |

| venue | National Museum of Western Art (Ueno Park, Tokyo) |

| Opening hours | 9:30-17:30 (until 20:00 on Fridays and Saturdays) |

| Closed days | Mondays, November 4th (Tue), November 25th (Tue), December 28th (Sun) – January 1st, 2026 (Thu, national holiday), January 13th (Tue) *However, the museum will be open on November 3rd (Monday, national holiday), November 24th (Monday, closed), January 12th (Monday, national holiday), and February 9th (Monday). |

| Admission fee (tax included) | Adults: 2,300 yen, University students: 1,400 yen, High school students: 1,000 yen

*Free admission for junior high school students and younger, people with physical or mental disabilities, and one accompanying person. (Student ID or proof of age, disability certificate required.) |

| Organizer | National Museum of Western Art, Musee d’Orsay, Yomiuri Shimbun, Nippon Television Network Corporation |

| inquiry | 050-5541-8600 (Hello Dial) |

| Exhibition official website | https://www.orsay2025.jp |

*The content of this article is current as of the time of coverage. Please check the official exhibition website for the latest information.