Taito City Ichiyo Memorial Museum

The Taito City Ichiyo Memorial Museum is currently hosting a special exhibition, “Shitaya Ryusenjicho, where Ichiyo lived,” showcasing Ichiyo Higuchi’s life in Shitaya Ryusenjicho (now Ryusen), the setting for her masterpiece, “Takekurabe.” The exhibition will run from Saturday, October 25th to Sunday, December 21st, 2025.

| ■ Taito City Ichiyo Memorial Museum <br />Thanks to the efforts of volunteers who came together to preserve the literary achievements of Higuchi Ichiyo, an outstanding female writer of the Meiji period, this museum opened in 1961 as Japan’s first literary museum dedicated solely to a female writer. Triggered by Ichiyo’s portrait being chosen to appear on the new 5,000 yen bill, the old, dilapidated building was renovated in 2006. Another highlight is the beautiful design by architect Yanagisawa Takahiko. The museum houses and exhibits a large number of valuable materials that convey Ichiyo’s creative activities and lifestyle, including unfinished manuscripts of “Takekurabe,” as well as letters and waka poem strips. |

The experience of living in Shitaya Ryusenjicho that fueled the “Miraculous 14 Months”

Higuchi Ichiyo (real name: Natsu) was born in 1872 (Meiji 5) into a middle-class family. She was gifted from a young age, and at the age of 14 she entered Nakajima Utako’s poetry school, Haginoya, where she studied classical poetry, waka poetry, and calligraphy.

In 1889, his father died of illness, leaving him with a large debt, and at just 17 he was forced to lead a difficult life as head of the household, supporting his mother, Taki, and younger sister, Kuni. He studied under newspaper journalist and author Hanai Tosui, and made his debut as a novelist with “Yamizakura,” published in the literary magazine Musashino in 1892. He tried to support his family with royalties from his writing, but was unable to escape poverty, so in July 1893 he moved from the quiet Hongo Kikusaka-cho to 368-banchi, Shitaya Ryusenji-cho, near the Yoshiwara red-light district, where he opened a general goods and candy store. He experienced the excitement of local annual events such as the Senzoku Inari Festival and Tori no Ichi, and spent his days observing the people coming and going in the red-light district.

In the end, his business did not get on track, and he ended up moving to Fukuyama-cho, Maruyama, Hongo after just over nine months. From there, he devoted himself to writing, publishing a succession of masterpieces, including “Takekurabe,” “Nigorie,” and “Juusanya,” based on his experiences living in Shitaya Ryusenji-cho. These were later described as “14 miraculous months.” He was highly praised by Mori Ogai and Koda Rohan, and received numerous requests to write, but he died of pulmonary tuberculosis in 1896, at the young age of 24.

The special exhibition “Shitaya Ryusenjicho, where Ichiyo lived” introduces the local characteristics of Shitaya Ryusenjicho, the fertile ground for Ichiyo to blossom as a writer, and unravels how she lived there, what she saw, and what she learned.

The poor tenement district where Ichiyo lived

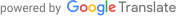

Upon entering the exhibition room, visitors are greeted by a model of Shitaya Ryusenjicho as it was at the time , recreated based on meticulous historical research and interviews. In the center are the two tenement houses where Ichiyo lived, and at the end of Daionji Street (now Chayamachi Street), which stretches straight out from there, you can see the stone wall and emergency gate of Ohaguro-dobu, which marks the boundary with the Yoshiwara red-light district. It is only a few minutes’ walk away.

| ■ “The lights reflected in the Ohaguro moat made it seem as if they were there, and the constant coming and going of carriages bespeaks an immeasurable prosperity. (Omitted) Turning the corner at Mishima Shrine, there was no visible large building, just a row of ten tenement houses with sagging eaves, numbering 20 houses in total…” (From the beginning of “Takekurabe”)

Modern translation: The commotion of the three-story red-light district, its lights reflected even in the blackened gutters, can be heard clearly. The volume of traffic, morning and evening, suggests the immeasurable prosperity of the area. (Omitted) However, once you turn the corner at Mishima Shrine, there are no large, conspicuous mansions to be seen, but rather a row of ten or twenty row houses with slanting eaves. |

| ■ “This house is on a single road that runs from Shitaya to Yoshihara. Since evening, the sounds of carriages flying by and the light of lights have been heard. It is a sight beyond words.” (From the diary “In the dust”)

This house is located on the only road that leads from Shitaya to Yoshiwara, and in the evenings, the sound of rickshaws echoes and lights flicker here and there. The scene is beyond description. |

Daionji Street, which connects Mishima Shrine to the Yoshiwara pleasure district, was a major route taken by rickshaws bound for Yoshiwara. When you look at the model together with Ichiyo’s words, the stark contrast between Yoshiwara’s vibrant lights, the bustling three-story brothels, and the constant traffic, and the shabby tenement district nearby, becomes clear.

Yoshiwara in the Meiji era – Children are also fascinated by Niwaga

“Takekurabe” is set in the Shitaya Ryusenjicho area and the Yoshiwara red-light district, and is an emotionally rich story that depicts the faint love between Nobuyuki, who will one day become a monk, Midori, who will become a prostitute, and their childhood friend Shotaro, as well as the conflicts they face as they approach adulthood, all set against the backdrop of seasonal events.

The story begins on August 18th, two days before the Senzoku Inari festival, and ends after the Third Bird Festival, around the end of November or early December, which overlaps with the period Ichiyo spent in Shitaya Ryusenji-cho. It is clear that Ichiyo’s own life experiences are heavily reflected in her work, and it is said that many of the characters were modeled after real people.

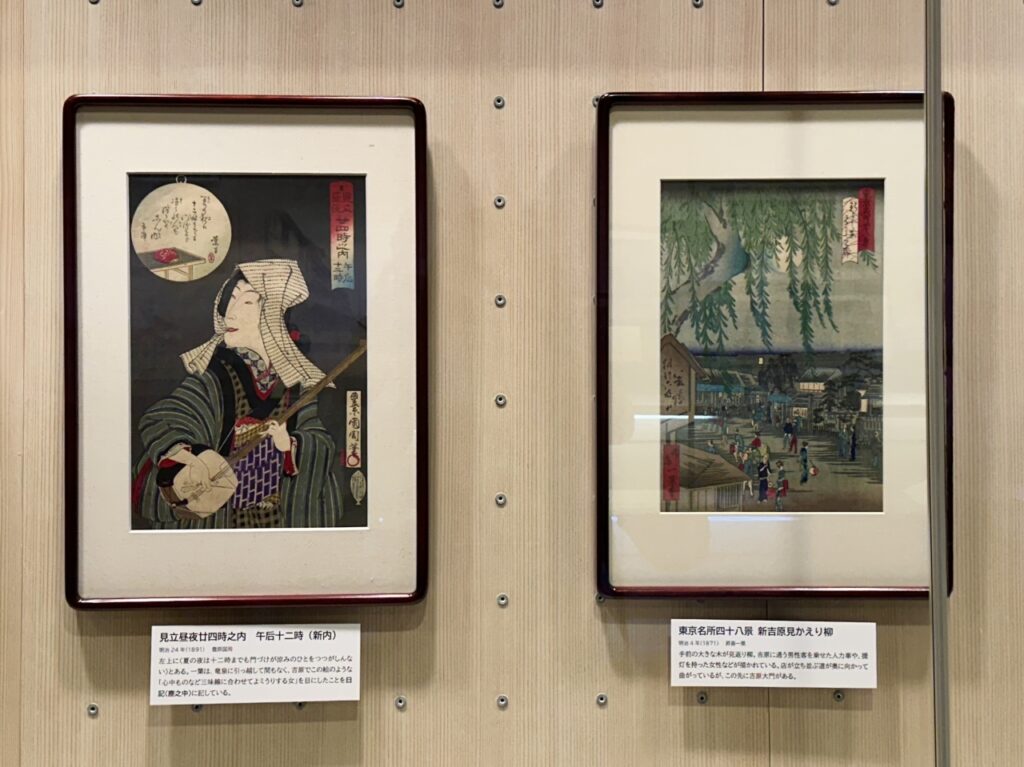

The hustle and bustle can be felt in the nishiki-e print “Nakanomachi Niwaka Iryou No Zu from Inamotoro, Corner Street of Shin-Yoshiwara,” which depicts the autumn Niwaka, an event that also appears in the work. This is an event where geisha perform impromptu plays at street stalls. In Yoshiwara, the spring Nakanomachi cherry blossoms (night cherry blossoms), the summer Tamagiku lanterns, and the autumn Niwaka are all popular as the three major views of Yoshiwara, and Ichiyo beautifully expressed the changing seasons by incorporating these into her work.

Bottom: Yoshu Shuen, “The Bustle of New Yoshiwara,” 1879

The story also depicts how the children, who have become completely immersed in the Yoshiwara atmosphere, begin to imitate geisha during the Ninwaka period, and Ichiyo writes with a hint of amazement at how quickly they improve, saying, “Mencius’s mother would be amazed.”It can be said that only Ichiyo, who actually lived in the area, could include such realistic impressions.

Ichiyo not only observed Yoshiwara from the outside, but also visited it herself. She heard about the circumstances of the pleasure quarters from the head maid of the Hikite-chaya teahouse who arranged work for her, viewed the Tamagiku lanterns, and took detailed notes on the age, clothing, and demeanor of the female courtesans performing the Shinnaibushi dance through the pleasure quarters… Each of these interviews would go on to shape the future Takekurabe.

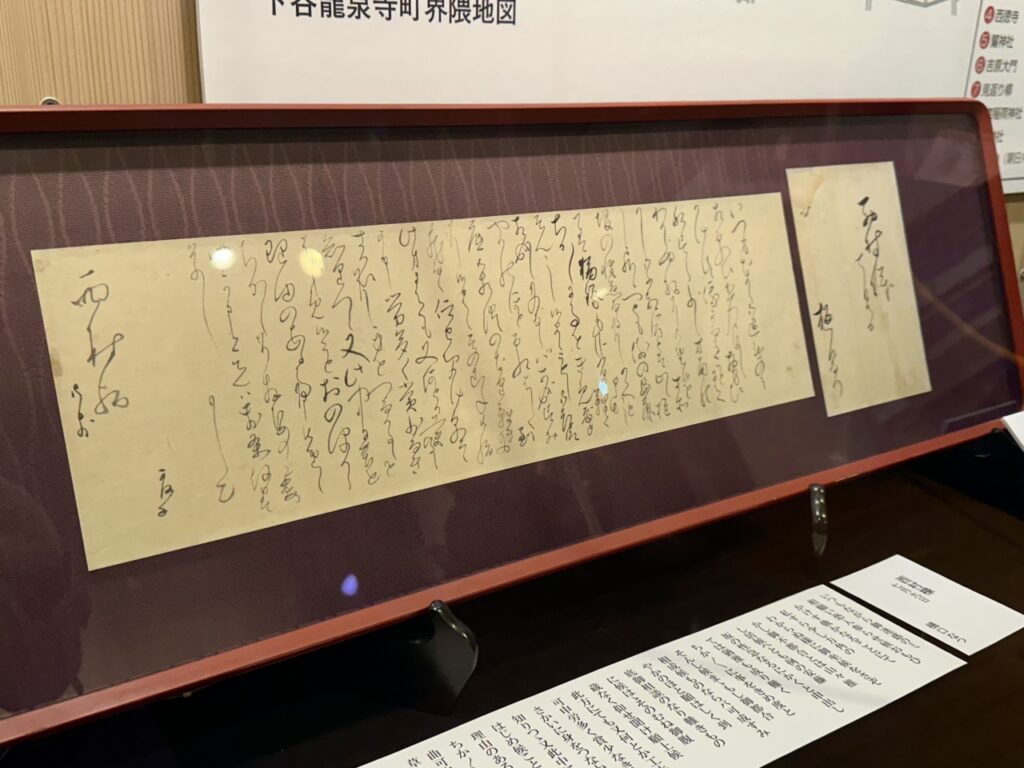

Days of trial and error at a candy store – and sometimes complaining

Ichiyo’s striking portrait is said to have been inspired by an entry in her diary “Dust Inside” dated August 6, 1893: “The sixth day, clear skies. I open the shop. (omitted) Tonight I load my first load, and it’s quite heavy…” August 6 was the shop’s opening day, and initially, the shop sold miscellaneous goods such as dusters, soap, scrubbing brushes, and Asakusa paper. Ichiyo soon realized that this alone would not be enough to make a profit, so she turned to a friend’s father, who ran a candy wholesale business, and began selling toys and cheap sweets such as menko, balloons, and illustrated books. She spent her days befriending the children who came to the shop.

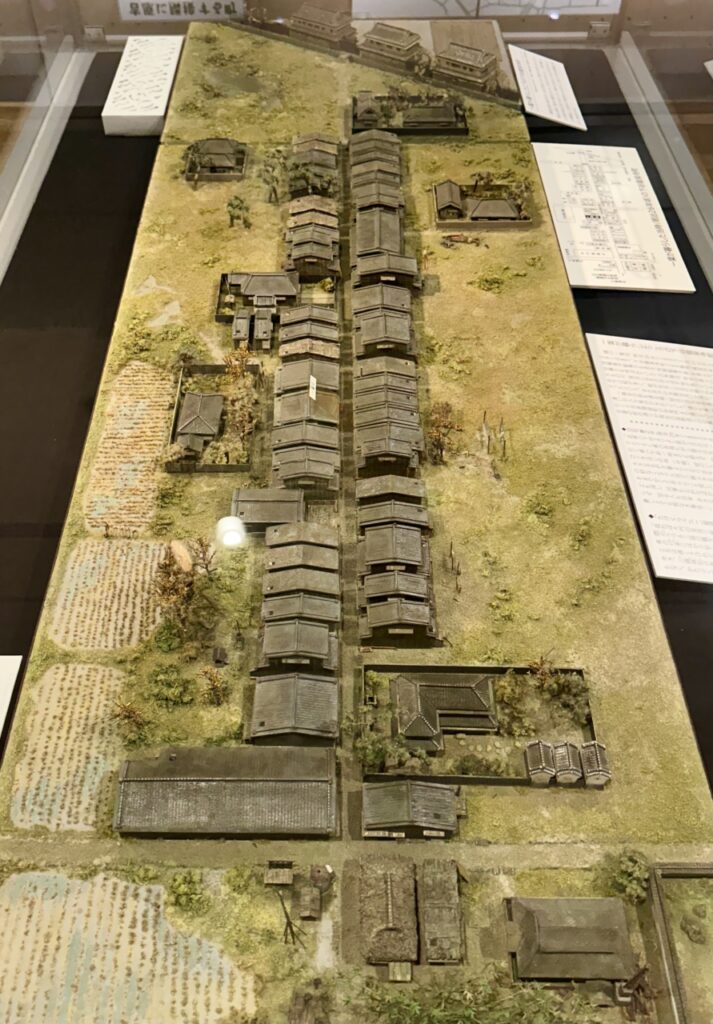

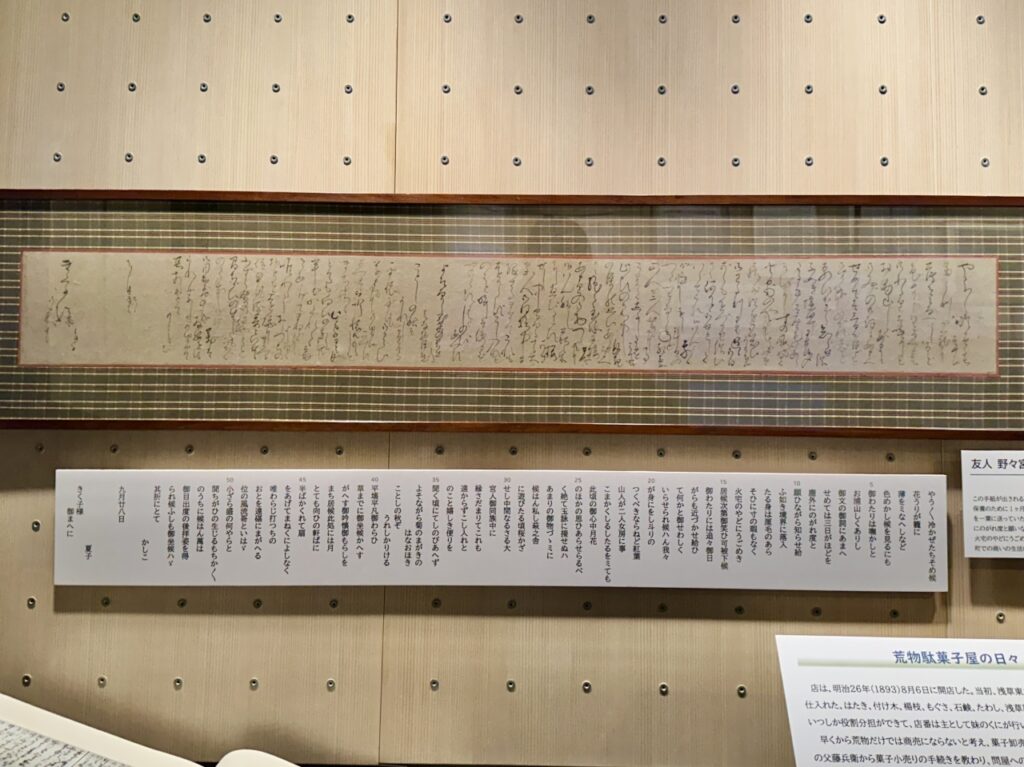

Although Ichiyo was so energetic that she would walk 20km a day in geta or zori sandals in the heat of summer while searching for a new place to live, she found the hectic pace of business difficult to bear, and her letters and diary contain many complaints. For example, when her friend Nonomiya Kikuko invited her to her hometown of Tako Town in Chiba Prefecture for a retreat, Ichiyo wrote:

| ■ “I hope to escape from the dust for at least three days… but I’m stuck in a burning house, squirming without a moment’s rest, battling the fury of my neighbors, and you’ll laugh at me.”

Modern translation: I wish I could escape from this troublesome world, even if only for three days, but petty problems keep popping up, I have no time for anything, and I struggle in my difficult living conditions. Please make me laugh. |

In his reply letter, he wrote about his situation with a hint of self-mockery.

Despite trying all sorts of help, business worsened when a competitor opened a shop on Chayamachi Street in January of the following year. In the end, he closed the store after just over nine months and moved to his new home in Maruyama Fukuyamacho, Hongo, where he decided to devote himself to writing.

Ichiyo returns to the path of novelist

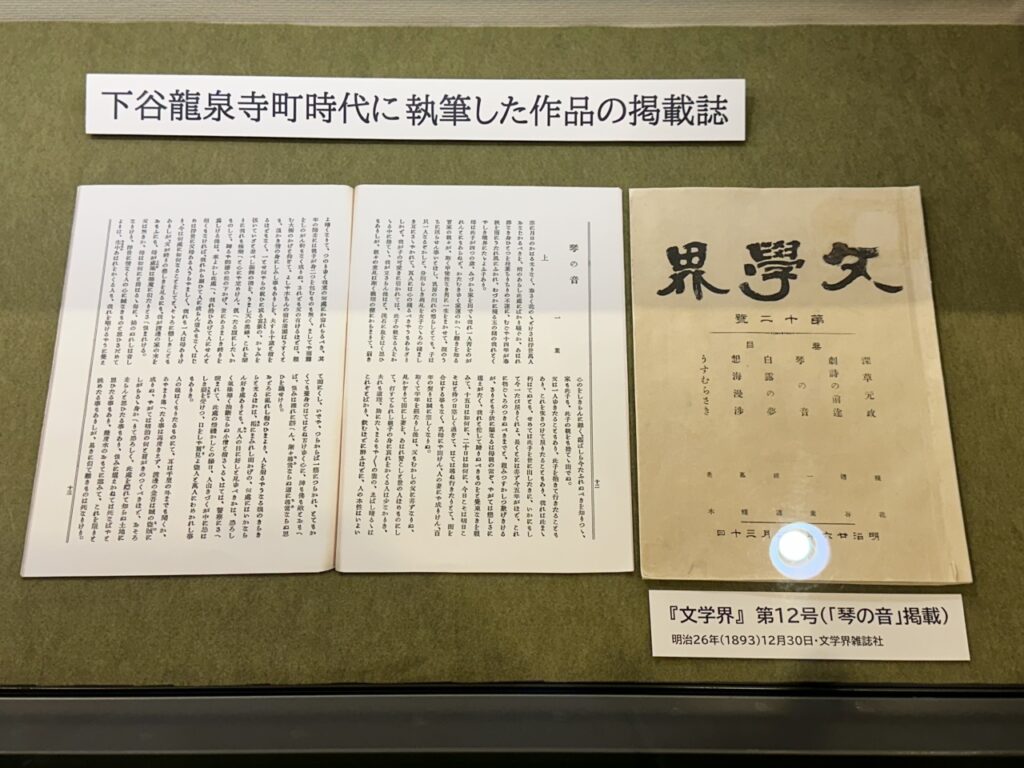

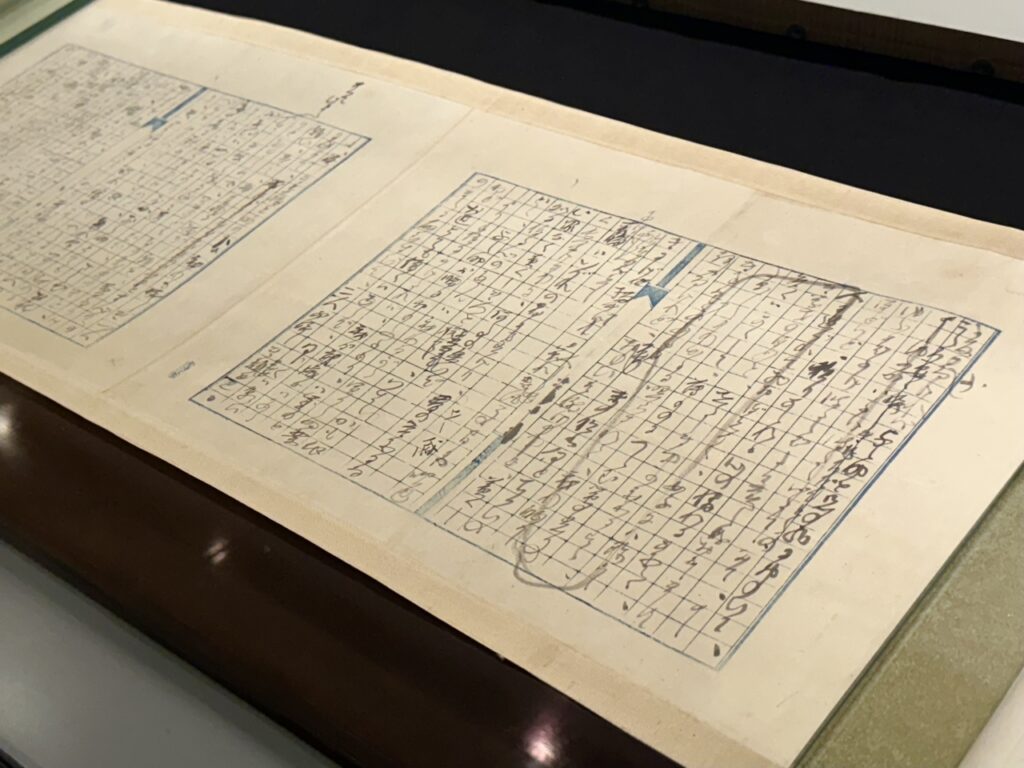

Incidentally, even while Ichiyo was living in Shitaya Ryusenji-cho and had almost completely stopped writing, writers Hoshino Tenchi and Hirata Toki, who had praised her talent for “Umoregi,” continued to patiently persuade her to continue writing despite her hesitation due to her busy schedule. As a result, she was able to publish two works, “Koto no Oto” (The Sound of the Koto) and “Hanagomori” (The Flowering Garden), in the magazine they founded, Bungakukai. This exhibition features an unfinished draft of “Hanagomori,” which shows signs of revision and significant deletions, conveying the pains of the writer, as well as diary entries describing the agonies she experienced while writing “Koto no Oto,” and the magazines in which both works first appeared .

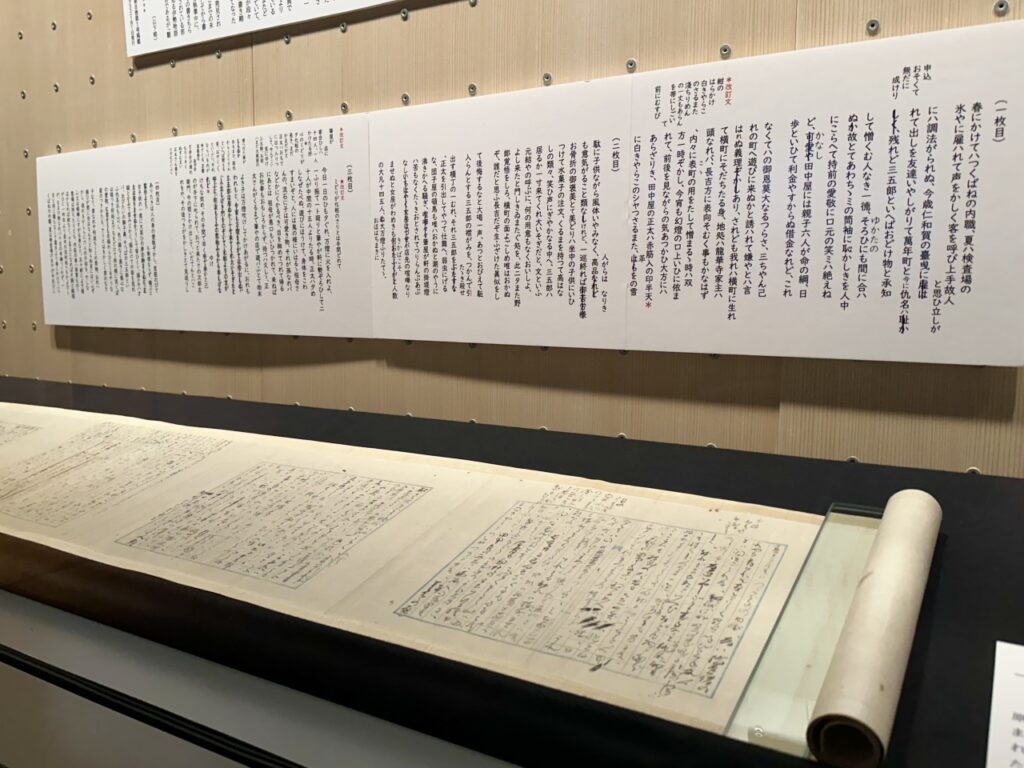

At the end of the venue , there are materials related to “Takekurabe,” including unfinished drafts, the origami book “Takekurabe Emaki,” and even books containing the manuscripts published in the “Bungei Club” magazine . The unfinished drafts are significantly different in content from the finished versions, so you’re sure to make new discoveries by reading them side by side.

Right: Shosai Ikkei, “Forty-eight Famous Views of Tokyo: Willows Looking Back at Shin-Yoshiwara,” 1891

Ichiyo’s early works featured a fantastical style, including mundane tales of tragic love, but her vivid experiences living in Shitaya Ryusenji-cho led to a more realistic style that sometimes captured harsh realities such as poverty and the plight of women. This exhibition showcases a major turning point in her creative career, which led to her being highly regarded as one of the leading writers of the Meiji period.

Additionally, there is a monument to the former residence of Higuchi Ichiyo on Chayamachi Street, about a two-minute walk from the Ichiyo Memorial Museum. The Ryusen area has changed significantly since Ichiyo lived there due to land readjustment projects as part of the Imperial Capital Reconstruction Plan following the Great Kanto Earthquake, but traces of the “single straight road from Shitaya to Yoshihara” still remain.

If you go east along Chayamachi Street, you will come across a pillar marking the location of the emergency gate to Yoshiwara Ageyamachi. In addition to viewing the special exhibition, why not take the time to imagine what the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter looked like from Ichiyo’s tenement house?

Overview of the special exhibition “Shitaya Ryusenjicho, where Ichiyo lived”

| Dates | October 25th (Sat) – December 21st (Sun), 2020 |

| venue | Taito City Ichiyo Memorial Museum (3-18-4 Ryusen, Taito-ku, Tokyo) |

| Opening hours | 9:00 AM – 4:30 PM (entry until 4:00 PM) |

| Closed days | Every Monday |

| Admission fee | Adults: 300 yen, elementary, junior high and high school students: 100 yen

* Free admission for those with a physical disability certificate, rehabilitation certificate, mental health and welfare certificate, or specific disease medical care recipient certificate, and their caregivers. |

| inquiry | Ichiyo Memorial Museum 03-3873-0004 |

| Official website | https://www.taitogeibun.net/ichiyo/ |

*The content of this article is current as of the date of the interview. Please check the official website for the latest information.