Tokyo National Museum

The national treasure “Haniwa Warrior with Armored Arms,” which is said to be the greatest masterpiece among the many different types of haniwa made during the Kofun period, has celebrated its 50th anniversary since being designated a national treasure, and a special exhibition commemorating this occasion, “Haniwa,” has opened at the Tokyo National Museum (hereinafter referred to as “Tokyo National Museum”). The exhibition will run until December 8, 2024.

Haniwa, which were actively produced from the 3rd to 6th centuries during the Kofun period, are unglazed sculptures that were lined up in burial mounds, the tombs of kings and other powerful people. Early on, they were simple cylindrical shapes, but as time went on, they developed into more and more unique pieces, including human figures, adorable animal figures such as horses and birds, and pictographs of elaborate weapons and houses. They are valuable materials that convey the lives and customs of ancient people to the present day.

This exhibition will bring together about 120 carefully selected treasures from around Japan, including haniwa and grave goods excavated from ancient tombs. This will be the first large-scale haniwa exhibition held at the Tokyo National Museum in about half a century.

Welcoming visitors at the entrance to the first venue is the adorable Haniwa Dancing People, with their playful expressions, which has now become a recognized icon of Haniwa. Haniwa, which emerged and developed uniquely in the Japanese archipelago, are characterized by simplified and rounded expressions in the clothing, faces, and gestures, but this representative work is filled with that unique “looseness .” It is said to depict people dancing in a ritual, and is also the model for the Tokyo National Museum’s mascot character, “Tohaku-kun.”

When it was excavated from the Nohara Tomb in Kumagaya, Saitama Prefecture in 1930, it was immediately repaired and restored, but in recent years it has deteriorated so much that it is no longer possible to lend it out. Therefore, the Tokyo National Museum and the Cultural Properties Utilization Center are raising donations through crowdfunding and other means, and will begin dismantling and repairing it in October 2022. Repairs are scheduled to be completed in March 2024, and this exhibition will be the first opportunity for the statue to be shown since its repairs.

There have been several changes since the restoration, but the biggest change is probably the intensity of the reddish color. During cleaning, it was discovered that the work had a stronger yellowish color than it actually was, due to dirt that had accumulated while it was buried and dirt in the air that had accumulated over the years of display. Old excavated items are often left with no effort to remove dirt, in order to show their history, but in this restoration, they decided to remove as much dirt as possible in order to allow the viewer to imagine how it was when it was first made. The original color that emerged is said to be a reddish burnt color that is rich in iron and contains volcanic minerals, a color that is often seen in northern Kanto.

Regarding the Haniwa Dancing People, according to Tokyo National Museum researcher Yamamoto Ryo, a recent theory that has gained popularity is that “rather than dancing, the figures are actually pulling a horse.”

Haniwa figures with one hand raised were often originally excavated together with horses. Also, it is possible that the twisted cord hanging from the waist of the shorter haniwa represents reins, and the sickle on its back represents an object used to cut grass for the horse. If it was a horse-puller, it would be a little disappointing, considering that we have been familiar with the “dancing people” for so many years…

“On the other hand, it is common for the meaning of the original haniwa to change as it develops. In this exhibition, we call them group figures of haniwa, but there are some that combine different types of haniwa to express various stories, such as a hunting scene using a hunter haniwa with a deer or boar haniwa. Therefore, depending on the combination of haniwa, there is still the possibility that they could have expressed a dancing scene, as has been said until now,” said Yamamoto. Further research is expected.

The next exhibition corner, titled “The Appearance of the King,” is a luxurious space where all the exhibits are national treasures.

The exhibition will introduce the National Treasure “Gold Inlaid Sword,” a sword with an unparalleled decorative pommel that was excavated from the Todaijiyama Tomb, built in the late 4th century. This sword, known as the oldest inscribed sword excavated in Japan, is said by some researchers to have been inherited by Himiko from the Chinese dynasty.

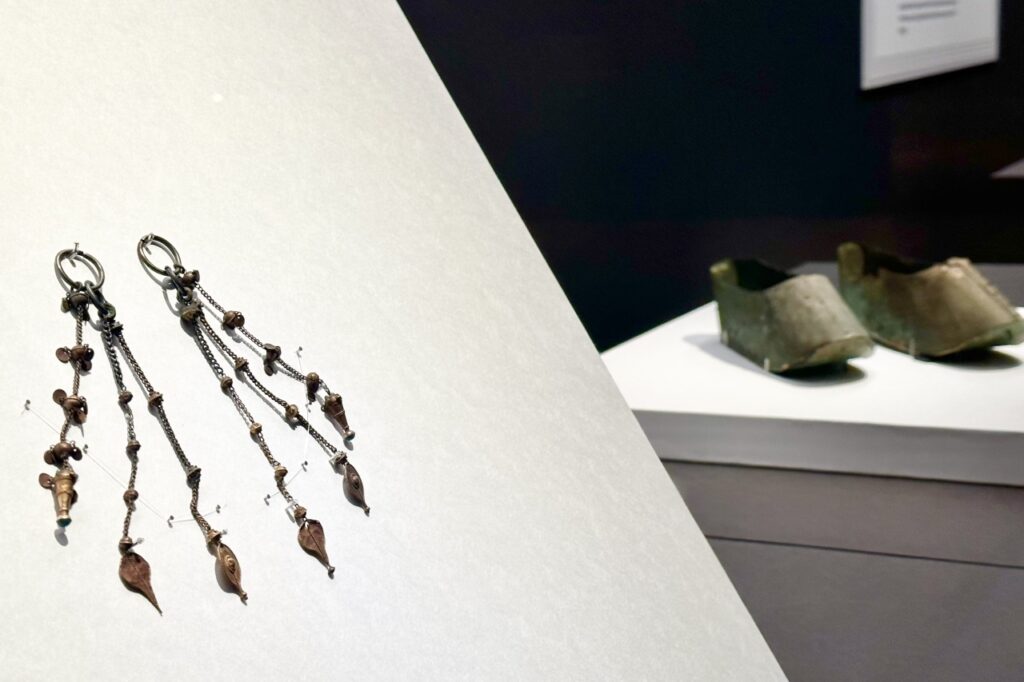

In the middle of the Kofun period (5th century), when the kings took on a more warrior-like nature in the wake of a period of upheaval on the Korean Peninsula, weapons and equipment became prominent. In the late Kofun period (6th century), when the centralized nature of the Yamato kingship strengthened and the custom of horse riding became more widespread, gilt bronze accessories began to appear, adorning the kings and their horses in splendid ways and showing their authority.

In this way, the grave goods changed in tandem with the changes in the king’s role, so by examining them, we can get a glimpse of how the culture and customs of the time when the haniwa were made were changing.

The custom of erecting haniwa in kofun burial mounds has spread throughout the Japanese archipelago, from the Kinki region, the center of kofun culture, to Iwate Prefecture in the north and Kagoshima Prefecture in the south, centering on the Yamato royal authority. As these haniwa developed, their individuality emerged in their expressions, depending on the differences in customs in each region, the proficiency of the craftsmen, and the strength of the relationship with the great king, from elaborate ones that are comparable to those in the tombs of the great kings to unique ones that are full of regional color. The “Haniwa Forms” exhibition corner focuses on the development of these diverse forms.

For example, the horse-shaped clay figure excavated from the Ishiyakushi East Burial Mounds in Suzuka City, Mie Prefecture, is unique in its straight mane or headgear, making it a rare specimen that is unseen anywhere else in Japan. The beard-bearded boy clay figure, said to have been excavated in Ibaraki Prefecture, resembles a fairy from a picture book with its curly hair and pointed hat. These clay figures with long beards are known as examples of highly regional styles from the 6th century.

What was secretly catching the visitors’ attention were the “Cylindrical Haniwa with Faces,” cylindrical haniwa that for some reason had facial features added to them.

The roots of cylindrical haniwa lie in earthenware called special vessel stands, which were used as ritual vessels in the Kibi region (present-day Okayama Prefecture) during the Yayoi period as stands to hold vases, and there is no reason for them to have faces. Cylindrical haniwa remained mainstream from the birth of haniwa until their disappearance, but there are only a few examples of cylindrical haniwa with faces excavated, mainly in northern Kanto, such as Shimogo Tenjinzuka Tomb in Tamamura Town, Gunma Prefecture, and Gyokidaira Sancho Tomb in Ashikaga City, Tochigi Prefecture. Perhaps it was the playfulness of a haniwa craftsman who thought, “A plain cylindrical shape is boring”?

As you enter the second venue, you will come to the highlight of the exhibition: the display corner for “National Treasure: Warriors Wielding Armor and Their Companions.”

The Haniwa Warrior in Armor , owned by the Tokyo National Museum, was excavated in Ota City, Gunma Prefecture, and is the first Haniwa to be designated a National Treasure. There are four other similar warrior Haniwa figures thought to have been produced in the same workshop as this one, which have been restored in perfect condition, but this exhibition will be the first time that all five of these “brothers” have been exhibited together in one place . One of these figures is currently in the possession of the Seattle Art Museum in the United States, making this a rare opportunity to compare the two.

The Tokyo National Museum’s collection is three-dimensional and elaborately crafted down to the smallest detail, and shows the figure covered in armor from head to toe, holding a bow in the left hand, a sword in the right hand, and a quiver (arrow holder) on his back. By the way, the armor on the upper body is made of small iron plates sewn together.

“There are no other examples of haniwa figures clad in such heavy armor,” said Masanori Kono, a researcher at the Tokyo National Museum.

“These ‘Warriors in Armor’ were made in the second half of the 6th century. Until the first half of the 6th century, the Kinki region, which was the cultural center of the time, led the way in haniwa making, and other regions followed suit. With the introduction of Buddhism, values changed, and the creation of keyhole-shaped tumuli and haniwa making gradually declined in the Kinki region. However, even in the second half of the 6th century, this influence had not yet reached Gunma, and haniwa were still being made enthusiastically. Gunma was extraordinarily enthusiastic about making haniwa, mastering extremely skilled techniques and leaving behind many haniwa that are representative of Japan.”

The five “Warriors in Armor” have very similar appearances, including their facial expressions, but on closer inspection there are some differences, such as the arrow holder they are carrying on their backs not a quiver but a koraku, which appeared later than the quiver, and hakama rather than protective gear worn on the lower half of their bodies.It is also worth noting that there has been a gradual omission of small details from the oldest specimen in the Tokyo National Museum’s collection, the Aikawa Archaeological Museum in Gunma, to the newest specimen in the Tenri Reference Museum attached to Tenri University in Nara.

Regarding this exhibition, Researcher Kono said, “I don’t want this to be just an exhibition of masterpieces. I have a strong desire to convey the latest research results to everyone in an easy-to-understand way, so I thought about the composition of the exhibition in light of the research results,” and cited the display of the color restoration of the museum’s collection of “Warriors with Armored Arms” as a prime example. Scientific analysis and detailed naked eye observation revealed that the entire piece was painted in three colors: white, red, and gray. This completely overturned the conventional image.

Towards the end of the exhibition, in the “Haniwa that tell stories” section, the focus is on the aforementioned “Haniwa Group Statues,” which combine multiple haniwa figures, including people and animals, to express various stories. The section introduces the role each haniwa played in the story, such as the “kneeling boy,” which represents a formal bow scene to praise the morality of the deceased king and pledge loyalty to the new king, and the sumo wrestler who stomps his feet to ward off evil spirits from the land on which the burial mound is built.

There is also a large collection of adorable animal haniwa here. The most commonly made animal haniwa is the horse, which was a symbol of power, but other figures such as roosters that herald the dawn, and deer, wild boars, and dogs that depict hunting scenes were also made in connection with royal ceremonies. On the other hand, some waterfowl and fish are thought to be faithful copies of animals in nature, and you can feel the natural creative consciousness of ancient peoples.

This large-scale haniwa exhibition was miraculously realized after about five years of preparation, in order to gather the top masterpieces from each collection. Why not take this opportunity to experience the profound depth of the world of haniwa once again?

*Photography is permitted in the exhibition rooms of this exhibition, with the exception of some works.

Summary of the special exhibition “Haniwa” commemorating the 50th anniversary of the designation of the “Keiko Warrior” as a national treasure

| Dates | October 16th (Wednesday) – December 8th (Sunday), 2024 |

| venue | Tokyo National Museum Heiseikan |

| Opening hours | 9:30-17:00

*Open until 20:00 every Friday, Saturday, and November 3 (Sun) *Last admission is 30 minutes before closing. |

| Closed Days | Monday

*However, the museum will be open on Monday, November 4th. *Only this exhibition will be open on Tuesday, November 5th. |

| Admission fee (tax included) | Adults: 2,100 yen, University students: 1,300 yen, High school students: 900 yen

* Free for junior high school students and younger, and people with disabilities and one caregiver. Please present your student ID or disability certificate when entering the building. |

| Organizer | Tokyo National Museum, NHK, NHK Promotion, The Asahi Shimbun |

| inquiry | 050-5541-8600 (Hello Dial) |

| Exhibition official website | https://haniwa820.exhibit.jp/ |

*The contents of this article are current as of the time of coverage. Please check the official exhibition website for the latest information.